John Himmelfarb & Percussionists — Rural Musicians Forum press release (Sep 2019)

A new piece of music, composed and performed on John Himmelfarb’s working truck sculpture named “KB-3,” will be performed Sunday at the Wyoming Valley School Cultural Arts Center in Spring Green.

Rural Musicians Forum closes the 2019 summer season with a multi-media performance showcasing an exciting collaboration between percussion performers, composers, and the celebrated American visual artist John Himmelfarb. This one-of-a-kind concert, taking place on Sunday, September 22, is the only performance that begins with the musical instrument being driven onto the stage.

Earlier this year, the award-winning Northern Illinois University students and faculty visited Mr. Himmelfarb’s vehicular KB-3 sculpture to build a collection of sounds through striking, scraping and bowing every part of the artwork.

For this special event, the RMF audience will witness a world-premiere of dozen works using Mr. Himmelfarb’s sculpture KB-3 as a musical instrument. This is also a unique opportunity to meet Mr. Himmelfarb and get familiar with his idiosyncratic, yet modernist-based work and his 5th artistic period called “Trucks.”

To add to the fun, some pieces will call for audience participation.

Bring your picnic chairs/blankets and join the Rural Musicians Forum for an unforgettable outdoor concert at the beautiful Wyoming Valley School Cultural Arts Center, located at 6306 State Hwy 23, Spring Green. Grounds open at 2 PM and music begins at 2:30 PM. Drinks and food will be available for purchase.

Please visit ruralmusiciansforum.org for tickets. Free entry for students with valid ID and children 12 and under. Rain shelter available if needed. To learn more about the Himmelfarb Project, visit himmelfarbproject.com. This project is made possible in part by funds provided by the Spring Green Area Arts Coalition and the Wisconsin Arts Board.

Among Friends: Ferguson, Himmelfarb share more than a space in their MAM exhibit — Janet L. Farber, The Reader (Dec 2018)

In the realm of the gallery exhibition, the two-person show is a tantalizing proposition. It suggests an opportunity to compare and contrast, not simply within a single artist’s output, but in the reflected light of another’s. Done well, this method amplifies our understanding of each artist by putting them into an interesting, relative context.

The current exhibition at Modern Arts Midtown hopes to do just this. Entitled John and Catherine, it features recent work by Chicagoan John Himmelfarb and Omahan Catherine Ferguson and runs through December 28.

The two are not only represented and shown regularly by MAM, but are also longtime friends. Hence the informality of the show’s title, suggesting that we viewers are welcome to share in a connection beyond happenstance.

At first, this may seem a little difficult to suss out. Himmelfarb is known primarily for his paintings, Ferguson for her sculptures and installations. Himmelfarb is a retro-modernist, plying motifs from daily life in the service of reawakening the formal pleasures of painting and the aesthetic rewards of seeing. Ferguson tends toward the conceptual, inviting the transformation of space and material into carriers of spirit and memory.

The exhibition itself also features work that initially feel a bit disparate. Himmelfarb’s big, bright and jaunty truck paintings contrast against Ferguson’s small-scale vector drawing-sculptures. Ferguson’s large-scale wire wall and floor sculptures, with their open volumes and shadow play, are more ethereal than Himmelfarb’s molten and welded truck sculptures under their burdens of cargo.

Yet, there is much rewarding commonality to be found in their creative endeavors. Each has shown an inclination toward eliciting degrees of whimsy, investing their forms with distinct personality. Both are essentially draftsmen at heart, displaying a distinct preference for the ways in which line creates shape, movement, volume and descriptive character. And despite Himmelfarb’s label as a painter and Ferguson’s as sculptor, each works across a variety of media. Himmelfarb works in bronze, steel, wood, lithography, etching and drawing. Ferguson’s media stretch across steel, wire, wood, hair, glass, willow, light, sound and found materials.

In fact, each new exhibition of Ferguson’s work reveals her in the midst of exploring some new thematic or material pursuit, and this show is no different. Debuting here is her fresh series of portrait heads collectively entitled All My People. Ferguson has turned quick vector sketches of individuals’ heads into laser cut relief sculptures and grouped them into small vignettes on steel shelves.

Whether the drawings are caricature or portraiture is ultimately a characterization made by the viewer, as the artist reveals little. Each may have a name — Harold, Lucy and Rhoda. Or be cast as a type — Adriatic Man, Beach Guy, Purple Scarf.

Inspired by a paraphrased quotation that “we all have 100 people inside us,” Ferguson has created a cast of characters reflecting the myriad of folks that have passed through both her life and imagination. It’s a world that certainly encompasses family and friends, yet this population of voices may also include those of writers, artists, fictional characters from art, theater, opera, film and literature, among others. There may also be those recalled from random encounters. And then there are those who inhabit our dreams.

Ferguson groups her figures together in pairs, trios and even quintets, encouraging our curiosity about their relationships — itself a kind of microcosm of this dual-artist exhibition. Her folks are quirky and charming. “Purple Scarf, Spike, Henrietta, Rhoda and Olga in Pink Hat” could, for example, all be part of a book club or serve on an arts committee with Ferguson. Or they could be totally arbitrary. It is our inclination is to fabricate a story that would connect them all to her, or even to us. They appear colorful and knowable, even with the economy of the artist’s drawing style.

Additionally on view are a pair of large scale sculptures created in powder-coated galvanized steel. Adapted from an older installation into discrete and now blue-colored sculptures, each stands on its own. “Del Castillo: Dancing” is in the form of a teardrop shape extended vertically into space, the stacked steel rods narrowing toward the center and expanding toward the top. With the suggestion of its title, the form takes on the animation of a person, bending slightly at the waist, with motion additionally implied by the play of lines on the floor and wall by cast shadows.

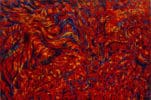

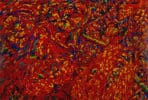

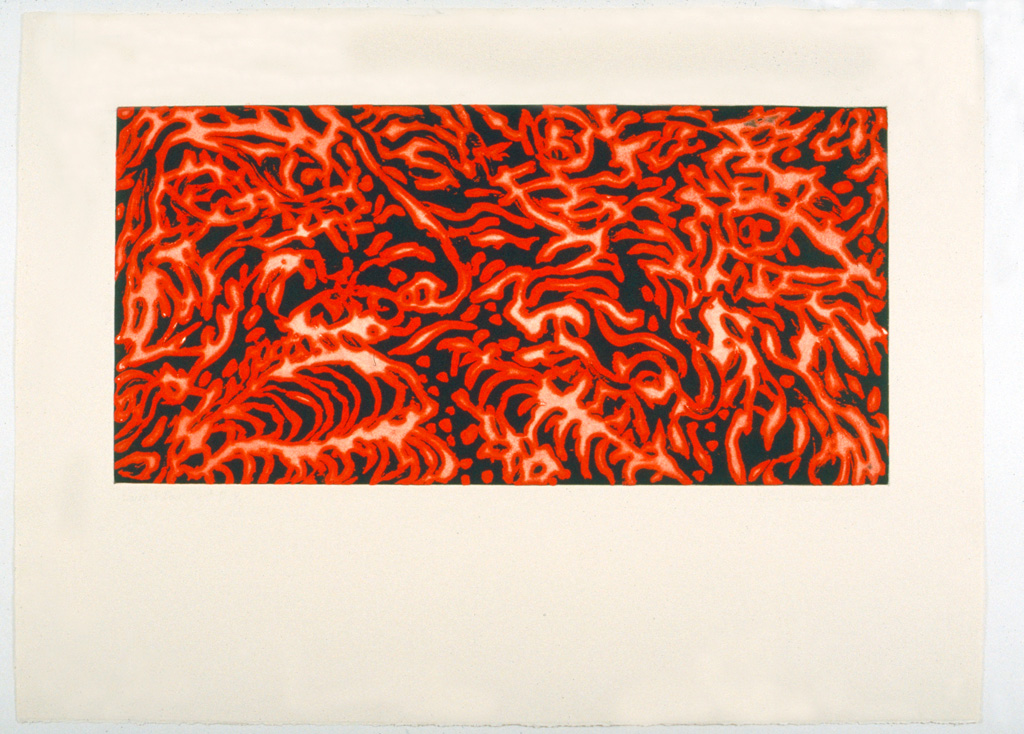

In Himmelfarb’s work, matrices of anxious line are more robust, sometimes pressed into service of bold expressionism that threaten to obscure the forms they describe. Among his ongoing series of truck images are the Puerto Vallarta paintings. Earlier examples consist of bright, two-color images inspired by an auto-driver’s eye view of the backs of semis and other rigs. The stylized patterns of lines gave the pieces an appealing graphic quality. Newer works from that series are denser and more painterly, as in Puerto Vallarta No. 89, with color palette more fiery and foreboding. The change in temperament may be interpreted as an attitude change about the vicissitudes of traffic. But for Himmelfarb it is just as likely to represent another turn in the leveraging of the simple motif into a vehicle for changing formal exploration.

A certain weightiness also appears in his large clear-coated steel sculptures. All the Names is a flat-bed trailer filled with neatly stacked load that comprise various sizes of cylinders, cubes, rectangular and triangular prisms. What the sculpture achieves with its industrial hue and hefty bulk is consciously offset by the toy-box whimsy of its cargo and the fantasy of irregularly ovoid tires and intentionally casual welds and cutouts.

Truly, what awaits the viewer in the main is the humorous side of Himmelfarb, who has recently added some new conceits to the sophisticated-naïve charm of his images and the word play of his titles. Check out The Gaze Returned, a large, prismatically colored canvas in which a truck is seen as a model on a pedestal in the studio, waiting to be incorporated by the artist into a landscape painting on an easel. In addition to all the other still life and studio tropes this describes, Himmelfarb has collaged a mirrored surface onto the truck’s windshield—literally returning the viewer’s gaze. Similarly, a vintage rearview mirror has been mounted atop the canvas of Ferry. “Come close and you can see yourself in the picture,” it intones, as if calling out our selfie-obsessed culture.

Equally clever and satisfying is Himmelfarb’s word/image play with Palette Truck. It depicts a flatbed semi with a precarious and colorful load of cargo spilling off its top and sides. Take another look—the wood on which this is painted is shaped and the back wheel of the semi is hollowed out, all in the form of an artist’s palette. This is Himmelfarb acknowledging literally that the truck is his springboard for artistic transformation, not a study of interstate transportation.

Just as some of Himmelfarb’s recent paintings demonstrate a return to a more formal simplicity, his new Icon sculptures are yet more restrained. These thin standing sculptures, made of powder coated steel or veneered plywood appear as totems built of graphic blocks or pixels—in a way, archetypes of a modern communication. They are the spiritual heirs to his prior works involving an invented vocabulary of symbols and hieroglyphs, out of which the truck motif originally arose. With titles like Architect, Leader and Local Hero, the sculptures aspire to be portraits, or at least frameworks for describing aspirational citizens.

So, what then to make of the pairing that is John and Catherine? It is a study in two artists dealing with issues of scale and line, of description and abstraction. It engages a duo who are rigorous and curious with their media, with the formalities of representation and the presence of the viewer. Who understand what is serious about their art but leave ample room for humor, as well as create the kind of play that engages the senses and the mind. Maybe that’s what friends are for.

John and Catherine continues until December 28 at Modern Arts Midtown, 3615 Dodge Street. For further information, contact 402/502-8737 or visit www.modernartsmidtown.com.

Postcard from Venice: Bridges, Bottles, and Madonnas — Matthew Rose, Artblog (Mar 2017)

Matthew sends us a postcard from Venice, where he spends time with artist John Himmelfarb and explores the inspiration offered by this magical place. —Artblog Editor

Venetian Retreat

Venice is a Byzantine labyrinth of water, stone, and brick and some 400 bridges criss-crossing a myriad of waterways. Getting lost is one of the special offerings of Venice. Wending your way through its intricate web of narrow, tapered streets, you are left with the sound of your own footsteps echoing through the centuries.

While John had never met Emily Harvey, the Fluxus art dealer who passed away in 2004, Emily created a foundation that would speak to artists for decades to come. “The opportunity to come and work in Venice—a city that is empty of cars, trucks, and wheels in general is a real gift,” said Himmelfarb.

“Much of my work had to do with urban materials—bridges, ironworks, construction cranes—a bird’s eye view of the city,” he explained. “When I applied to the EHF, I wrote that my work was architectonic with a nod to the idea of map making.”

Chicago-based painter and sculptor Himmelfarb’s recent projects consist of drawing, painting, and assembling trucks—both toy-sized sculptures and actual vintage pickups loaded with an assortment of rusted objects and found detritus. His works are a kind of history on wheels, sojourners in time. And Venice, with its pronounced absence of cars—and wheels in general—proved an interesting place to uncover the essence of our attachment to motion and John’s current interests.

In his studio near the Mercati di Rialto and the Pescheria (the fish market), Himmelfarb had produced a small truck painting that mimicked, in its patterning, the Venetian sestiere (districts) as they are sliced up by the network of canals that spiderweb through Venice. Traghetto (2017), a 9×12” acrylic on paper, employs Himmelfarb’s signature line work and riffs off the pushcarts the city employs to ferry the garbage from the streets to waiting trash boats.

Peggy’s House

I asked Himmelfarb what he’d seen in his first few weeks. A tour of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection yielded, he said, a 20th-century view of Modernism and Conceptualism. Guggenheim was an American icon in Venice for decades. She famously launched the Art of the Century gallery in New York just as World War II cast its pall over Europe, and she created an aesthetic home for most if not all the Surrealists in New York. Her home in Venice features a world class art collection that attracts tens of thousands of visitors annually.

In one of the galleries, John said he was particularly drawn to Tony Cragg’s “Bottles on a Shelf” (1981). Known for his reclamation of objects washed by time and sometimes the oceans, Cragg placed five plastic bottles on a painted wooden shelf. It’s all quite simple and direct, and probably puzzling to the average viewer, but Cragg helped to rewrite the book on sculpture, oftentimes arranging bits of washed up plastic spilling off a wall to the floor. His innovations echoed movements in the 1950s and early 1960s that removed the pedestal from sculpture, embraced life in the use of ordinary objects and focused on immediacy.

“The Cragg reads very flat,” said Himmelfarb, almost like the Ellsworth Kellys in the next room. “The bottles were most certainly washed up along some shore; I’ve used things that have been cast away and moved through the cycle once. I see this piece not as just a concept about recycled work, but a stab at realism in primary and secondary colors.”

Miracles & Madonnas

I had to take John and his wife, Molly, who accompanied him on this trip, to one of my favorite churches in Venice the Chiesa di Santa Maria dei Miracoli (1481), the marble, box-like structure designed by Pietro Lombardo (c.1435-1515) to house and protect a single painting—an icon of the the Virgin Mary with Child. This prime example of Venetian Renaissance architecture is one of the more severe of Venice’s 139 churches. It is empty of much of the Christian objects one finds in other churches here, though the vaulted ceiling is decorated with portraits of religious prophets. The “Church of Miracles” was the object of a 10-year “Save Venice” campaign to keep it from bursting apart from salt, a constant worry in a city that is regularly inundated by rising sea waters, a reality exacerbated by global warming.

Sitting in a lagoon in the north Adriatic, Venice is a work of art in itself, but it is also surrounded by other islands that were once more important historically and commercially. Himmelfarb told me about a visit to Torcello, an island some 40 minutes from Venice by vaporetto (boat) to see the ancient basilica there. First constructed in 639 and enlarged several times since, the church was once the capital of Christianity in Northern Italy before Venice’s San Marco drew both commerce and the faithful. Within the main apse of the medieval basilica, a standing 11th-century mosaic of the Virgin with child overlooks the congregation.

“The Madonna consists of thousands of mostly dark blue tiles,” said Himmelfarb. “And she is like a giant Giacometti surrounded by an enormous, minimalist field of tiny gold mosaic tiles. It’s hard not to be fascinated with the workmanship. Great works of art are always religious experiences.”

If not a religious experience, walking in Venice, though ordinary, provides a unique kind of awareness. The hundreds of foot bridges everywhere are each “a little sculpture,” Himmelfarb noted. “Venice forces you to really consider construction, movement and urbanism in its most basic manifestation; the bridges and their design and their site specificity—changing elevations, odd angles — gives breadth to notions of measurement, material, direction, and intimate and public spaces.”

“You can’t get around Venice very easily without looking at maps. And scale is different here, of course. But in Venice you’re on foot and walking here is like wandering around inside a sculpture — moving from open and closed spaces. Endlessly interesting — the pavement, the water, smooth and rough textures of the brick and stone — you feel as if you’re in a work of art.”

John Himmelfarb at Sioux City Art Center — Sioux City Art Center (2016)

Himmelfarb is one of the most respected artists of the Midwest. His work spans virtually all mediums, including painting, drawing, and printmaking, as well as sculptures in metals, ceramics, and found objects. His current and continuing series of works focuses on trucks as a subject. In Himmelfarb’s own words, “These works are not about trucks but about us, our histories, skills, coping mechanisms, ambitions and character.” The Atrium will exhibit a number of his larger sculptures, while the 3rd floor galleries will present smaller sculptures and wall-mounted work. The exhibition will also include one of Himmelfarb’s “life-sized” truck sculptures, such as Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain, a 1946 Chevrolet farm truck that has been converted into a mobile sculpture.

The show will be complemented by the 124-page book, John Himmelfarb: Trucks: Recent Works, published in 2014. This exhibition has been sponsored in part by the Martin/Seamster Fund.

Trucks take over the Sioux City Art Center — Ally Karsyn, Sioux City Journal (Jul 2016)

At first glance, maybe it looks like a jalopy broke down in front of the Sioux City Art Center, but that’s just Penelope — and her creator wouldn’t be too happy if someone hauled her away.

John Himmelfarb, a Chicago artist, converted the teal-cabbed 1946 Chevrolet 2.5-ton farm truck into a mobile sculpture, heaped high with a rusting pile of junk.

Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain is the most visible work in his exhibition, Trucks, which opens with a free public reception from 5-7 p.m. Saturday at the Sioux City Art Center, 225 Nebraska St. Himmelfarb will give a gallery talk about his paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures at 6 p.m.

Several of his larger sculptures will be displayed in the atrium while smaller sculptures and wall-mounted works will be in the third floor galleries through Oct. 23.

Here’s what you need to know before you go:

1. Himmelfarb is driven by the captivating visual qualities of trucks.

Himmelfarb has been making art for nearly 50 years. His earlier works varied in style and subject matter, featuring abstracts, pictographs and calligraphic marks. Around 2003, trucks became the central focus of his new works and he began making more sculptures.

“I’ve drawn trucks since as long as I can remember,” he said. “I came across a drawing I did when I was about 8 years old, and it had trucks in it. In the past, a lot of my works have had a variety of objects in them, but there were lots of them and small. So there might be a plane or a cup of coffee or a house and a cloud. A lot of different things. There were trucks among those, but the truck was never the main subject.”

2. You can think what you want.

“People want to know what my work means,” he said. “I just go with my gut feeling and worry about what it might mean, if anything, at a later date.

“I want people who look at my work to feel free to think about it on their own terms and figure out what it might mean to them. What they bring to it and what they take away from it is a personal matter. There’s not a right or wrong answer. They don’t have to figure out what I was thinking about because I wasn’t thinking about anything, except the forms and the shapes and the colors and some visual excitement.”

3. The truck outside the Sioux City Art Center came with a name.

Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain is the third life-size truck sculpture created by Himmelfarb. When he purchased the Chevy, the previous owner told him that the truck’s name was Penelope and she would run better if he talked to her.

Like taking home a traumatized pound puppy, Himmelfarb figured he better not change the name. Penelope’s life had been tough enough. Her name wasn’t all bad, either. In Homer’s “Odyssey,” Penelope is the clever, virtuous wife of Odysseus, who waited over 20 years for him to return home. The second half of the sculpture’s title gives a nod to the late John Chamberlain, a famed sculptor who often used scrap metal auto parts as a medium.

4. The truck sculptures are fairly eco-friendly.

Himmelfarb works with found objects and uses details of those objects to determine a color palette. For example, Penelope came with a teal cab and he didn’t change it. Instead, he brought more pops of the deep blue-green into other objects stacked onto the truck.

“I like using things that have been used before,” he said. “The less energy and toxic materials that are needed to make the whole thing, the better it is from my point of view.”

5. There are four other trucks like Penelope.

Penelope is actually part of a series of life-size sculptures built on real trucks.

The first, Conversion, was built on a 1949 International pickup. Marc LeBaron, chairman and CEO of Lincoln Industries, and his wife Kathy bought the piece and installed it on the company campus in Lincoln, Nebraska.

The second, Galatea, started with a 1948 REO Speedwagon. Contemporary art collectors Robert and Karen Duncan, also from Lincoln, bought this one and installed it in their sculpture garden. Penelope is the third truck, and there are two more, KB-3 and Remains.

6. Penelope still runs.

Himmelfarb took the engine out of the first truck, thinking museum curators wouldn’t want to deal with gas and oil leaking on their floors.

“I’ve since realized it’s a lot easier to leave it in,” he said. “Even if it’s going to be shipped on a trailer, at least you can drive it onto the trailer and off the trailer without having to tow it.”

She’s a little top-heavy, but Himmelfarb drove Penelope about 30 miles from his art studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, to an outdoor exhibition site for Fermentation Fest, where farmers, chefs, artists, poets and cheese makers converge in the beautiful working lands of Sauk County with a series of tastings, demonstrations, cooking classes and art events.

7. Himmelfarb had a solo show at the Sioux City Art Center in 2000.

The exhibition, Floor to Ceiling, featured a lot of abstract works with an urban quality. He was inspired by city infrastructure like the iron work on bridges, cranes and railways. He experimented with layers of colors and patterns to create a series called Inland Romance. “It began to look like if you had built something elaborate out of Tinker Toys and taken it apart and left those parts around,” he said.

Honk for Himmelfarb: Auburn’s new art exhibit — MiKyle Crockett, Opelika-Auburn News (Feb 2015)

Pushing the limits of artistic mediums, Chicago artist John Himmelfarb brings a new art exhibit, TRUCKS, to the plains. Consisting of sculptures, paintings, drawings and an actual truck, his exhibit is diverse and engaging for all ages.

One of the main eye-catching pieces from the exhibit is titled, Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain. It is constructed out of a 1946 Chevrolet truck, along with additional materials, and currently positioned in front of the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art.

“The first time I drove Penelope at any distance was about 35 miles on rural roads, up big hills. I’ve driven through snow and ice to deliver the sculpture,” said Himmelfarb, according to ocm.auburn.edu.

“Truck drivers would come over to see what I was hauling pretty much everywhere I went. It generated a lot of conversation. People would stop and say ‘my grandfather had a truck like this one.’ People loved to have their pictures taken with it and would bring their kids.”

To demonstrate his techniques and passions, Himmelfarb was welcomed back to the Plains to complete another main piece located inside of the museum. The 35 feet long mural is titled Grace.

“These works are not about trucks,” Himmelfarb said. “But about us, our histories, skills, coping mechanisms, ambitions and character.”

According to RoGallery.com, Himmelfarb “has occasionally incorporated truck imagery in his work, usually in an ancillary role, or as a single character in larger, more complicated pieces. In more recent years, he has been using the image of a truck as the central organizing principle in his paintings, drawings, prints, and now in sculpture.”

To compliment the exhibit TRUCKS, the museum will pair it with a film series called FILM@JCSM: American Transport. This series will take place Thursday, Jan. 29 from 4 pm to 5:30 pm.

The second series linked to the exhibit, K-12 Art Club: Keep on Truckin’, will take place on March 15 at 1:30 pm.

Complementary tickets available and reservations are encouraged for each event. This exhibit will be held at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art from January 24-May 10, 2015.

Auburn second graders talk “Trucks” — Katherine Haas, Opelika-Auburn News (

One group of second-grade students had a truck-themed school day Tuesday; however, there was no exhaust to smell, there were no horns to honk nor were there engines rumbling.

Second graders from the Auburn Early Education Center had the opportunity to visit Auburn University’s Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art to meet and interact with artist-in-residence John Himmelfarb , whose exhibition “TRUCKS” began Jan. 24 and will be on display through May 10.

In addition to asking Himmelfarb questions about his work, students watched as he worked on his 35-foot by 12-foot mural, Grace, in the museum’s Bill L. Harbert Gallery. Himmelfarb will be working on his installation mural in the gallery through Friday.

“To help the kids see the process of being an artist and see that art is important,” said Lauren Duncan, art teacher at AEEC. “It’s important in our community, and it’s meaningful in our society.”

Himmelfarb’s “TRUCKS” features works both two-and-three-dimensional works made from a variety of mediums including clay, lead, wood, steel, iron, acrylic paint, ink, crayon and unconventional materials, with trucks as an American icon at its core. Rather than depicting literal translations of trucks, Himmelfarb’s works evoke the individual personalities and purposes of trucks in an expressionistic style. The size of his works ranges from small drawings to life-sized actual trucks, such as his Penelope Awaiting her Chamberlain, created from a 1946 Chevrolet truck and found objects.

Penelope, currently situated for viewing on the museum lawn, was one of several works that students were able to view on Tuesday as they visited the museum.

“They’ll be going through all our exhibitions. We also have some works from our permanent collection on view,” Charlotte Hendrix, print and digital media producer for JCSM, said Tuesday. “And our docents will walk through with them and really encourage a conversation-style tour as opposed to just one person talking the entire time. It’s really a give-and-take, and that’s somewhat what John’s artwork is about. He enjoys engaging conversation, so that’s one of the reasons why he was able to come here and paint in public.”

Hendrix added that trucks are a relatable subject matter for the children.

“You’ll see a lot of the line and color — it’s very whimsical; it’s very fun,” she said. “And it’s something that they have a great familiarity with. Many of them play with trucks, or maybe their dad has a truck, or they’ll see them on a road trip. For the viewer, there is some kind of connection to truck, and that’s one of the reasons John has said he has chosen this as his subject matter, because it’s such an American icon.”

Himmelfarb, who is based in Chicago, said his decision to focus on trucks in his work was twofold.

“I think initially it was because they’re visually interesting,” Himmelfarb said. “The shapes, the colors, the textures—there’s a huge variety. When people think of trucks they tend to think of a tractor-trailer and a box behind it and they say, ‘What’s interesting about that?’ But when you actually start to look at the variety of vehicles out there, there’s a lot of lines and textures and colors, even if you just look at the back of the truck—all the old signs on it, lettering, hinges and door locks. You begin to find patterns and shapes that are interesting.”

In addition to being visually interesting, Himmelfarb explained how trucks are also a metaphor for people.

“After I worked with them for a while, I realized there was a hook of some sort that was more of an emotional hook to it,” he said. “Then I realized that handled in a certain way, they’re a metaphor for us. These works are not really about specific trucks. These are stand-ins for people for our experiences. So the variety in these trucks reflects the variety in our experiences.”

Duncan echoed Himmelfarb’s idea of trucks as a metaphor, adding that Himmelfarb’s expressionist style appealed to students.

“They love the theme of the trucks, they love the bright colors, and also I think they relate well to the way that John Himmelfarb works with his loose brushstrokes, very expressionist, lots of energy in his artwork,” Duncan said. “But the truck is so cool because it symbolizes more than just trucks. The truck is symbolic of people, and the things that are inside of the truck are symbolic of the things we carry with us and the burdens of all these different things. So it’s cool because it’s got the layer of fun, whimsical, colorful truck, but it’s also got a layer of very, very meaningful art.”

Himmelfarb painted Tuesday while students watched and asked questions. He said he intended to teach students about colors and lines and how they play into an overall design.

“I’m also trying to share with some of them the idea that in order to make something good, you have to be willing to make mistakes,” Himmelfarb said. “Otherwise, things don’t develop without making trials and errors. So I’m hoping they learn from that not to get frustrated if they’re making something and it’s not going right. They shouldn’t feel like they’re a failure. They should just keep going—just keep at it.”

Sarah Clark, 8, said that her visit to the museum did teach her that mistakes do not necessarily ruin an art piece.

“I enjoyed learning that John Himmelfarb doesn’t know what he’s about to paint,” Clark said. “He just starts painting, and then if he doesn’t like something, he paints over it.”

Andrew Hamner, 8, said he enjoyed the variety of truck elements that appear in Himmelfarb’s mural-in-progress.

“My favorite part was seeing all the different paintings crafted and knowing what they’re made of,” Hamner said. “I really liked how it had all sorts of different kinds of trucks features, like the ladder and the firetruck—all sorts of other things.”

Both Duncan and AEEC Principal Shelley Aistrup said that they were excited for the chance for their students to be able to interact with an artist first-hand and know that the art world is more accessible to them than they may think.

“Sometimes I think that when we talk about artists and poets and authors, children think that that’s something that’s unattainable to them, so I hope that this allows them to see that painters are real people, and this is something that they could strive for and accomplish in their lifetime as well,” Aistrup said.

“I just think the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art is a fabulous resource in our community, and I love getting to plan a trip to get my kids inside the museum, so they see it not as this marble building on a hill, but a place where they can come interact and learn and play,” Duncan added. “For them to interact with a real artist is a huge opportunity. So not only are they in the museum; they’re seeing this process, so it’s really cool.”

Unique art exhibits roll onto campus — Victoria Bruick, Valparaiso University Center for the Arts, Valparaiso, IN (Jan 2014)

Why’s there a truck outside the Valparaiso University Center for the Arts? The Brauer Museum of Art opened three new exhibits last week including “Trucks: Recent Work by John Himmelfarb.” The teal truck piled high with old cans and barrels is entitled, “Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain” and is part of the multi-medium art exhibit located in the museum’s Wehling and McGill Galleries. Additionally, Gallery 1212 currently houses “Mr. Imagination: Chicago Self-Taught Artist,” and the Education Room contains “Modern Vision: Japanese Prints from the Ruth A. Ruege Collection.”

Himmelfarb’s exhibit features sculptures, prints and paintings all depicting abstract trucks. The titles of his pieces often lend to deeper threads of inspiration such as, “Wisdom,” “Mesa” and “Sweet Surrender.”

In a note from the artist, Himmelfarb wrote, “My primary driver as a visual artist is to create form that is exciting visually and that suggests content ripe for interpretation through association, metaphor, and implication. I am not concerned with illustrating what we see.”

Additionally, director and curator of the Brauer, Gregg Hertzlieb included, “Through Himmelfarb’s treatments, the truck becomes a carrier of meaning, a vehicle for representational approaches, that speaks to its humble utilitarian nature at the same time it showcases the artist’s considerable and diverse skills.”

The full size truck sculpture outside the vehicle is drivable, according to Hertzlieb. It will be housed on the lawn between the VUCA and the Harre Union until the exhibit closes in April.

Senior communications major and theater minor, Rachel Abbinante works at the museum’s front desk. “I think [the truck] is really awesome because it will get people into the gallery to see… what we have to offer both in our permanent collection and the Mr. Imagination collection that is also on display,” Abbinante said.

Art collectors Sherry Siegel and Robert Alter generously allowed the Brauer to showcase the work of Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack, 1948-2012). The native Chicago artist is known for his use of found materials and sandstone sculptures.

Siegel said she and her husband began collecting Mr. Imagination’s work around 2000, and they now own 100 of his pieces that range from small jewelry to sculptures several feet tall. Not only did the couple collect his work, they also were personal friends of the artist.

“He was very, very, very generous,” Siegel said. “He was always giving gifts to everybody. If I had an aunt that had a birthday she got a gift. If I had a mother that was sick, she got a gift. Everyone in my family has a present from him. He was a just a generous soul, and he did that for everybody, not just for me.”

The artist referred to himself as “Santa Claus, all year round.” The exhibit captures not only the artist’s talent, but his love for others and his special relationship with Alter and Siegel. Included are gift boxes personally signed from Mr. Imagination himself to family members of the collectors.

“I think his generosity is really important, and I think it’s why so many people all over the world loved him,” Seigel said.

The third exhibit, “Modern Vision,” features Japanese Prints from the twentieth century and is part of the Ruth A. Ruege Collection.

Hertzlieb provided context to the collection.

“Ruth Ruege is a retired librarian who collects Japanese prints… She’s been collecting Japanese prints for many years, and she’s developed a really top notch collection,” Hertzlieb stated.

In collaboration with curator Dr. Sandy Kita from Washington D.C., the Brauer showcases prints that contrast the older, more traditional Japanese prints with which most people are familiar. The modern prints reveal much about the effects of World War II on Japanese artists. More information about the exhibit and the artists is provided by the curator in the Education Room.

All three exhibits through color, creativity and imagination welcome visitors to stop and explore each of their distinct perspectives.

“Art is usually serious, but it doesn’t have to be super serious. It can be fun,” Hertzlieb said. “When you’re going to college, it’s the time and opportunity to experience and see new and unusual things so you can learn. We hope people will look at this and say number one, ‘It brings a smile to my face and I like that,’ and number two, ‘I’ve never seen art like that before and even if I don’t like it, at least it’s new and I gave it a try.’”

The Brauer Museum invites all students, faculty and Valpo community members to check out the spring exhibits as well as the museum’s permanent collection. Hours are posted online as well as on the museum’s door.

Upcoming events at the Brauer include a Gallery Talk with John Himmelfarb on Wednesday, Jan. 22 at 7 p.m. and a Student Coffee Hour with Mr. Imagination Collectors Robert Alter and Sherry Siegel on Wednesday, Feb. 5 at 7:00 p.m. Additionally, a birthday celebration commemorating the life of Mr. Imagination will take place in the Brauer on March 30. All three exhibits will be featured in the Brauer until April 6.

New Foundation to Focus on Publishing Art Books — Patricia Cohen, The New York Times‘ Art Beat blog (Jan 2014)

Art books, monographs and catalogs are essential for historians, collectors and artists, but they rarely make money. Often oversized and lavishly illustrated on high-quality glossy paper, they are expensive to produce for the relatively tiny number of institutions and individuals who buy them. Enter the Artist Book Foundation, a new nonprofit organization dedicated to publishing fine-art references that otherwise would not be seen. Next month, it will release “Trucks: Recent Works by John Himmelfarb,” to accompany a new traveling exhibition of that Chicago artist’s work that opened last week at the Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University in Valparaiso, Indiana.

“Think of the Artist Book Foundation as a museum in print,” said the New York artist and printmaker Tom Slaughter. Smaller institutions often cannot afford to publish exhibition catalogs. The foundation plans to document and distribute a visual record of work that would otherwise hardly be seen. Ten percent of each print run will be donated to public, art and university libraries, said Gibb Taylor, who founded the foundation with Leslie Pell van Breen.

“Trucks” is part of the foundation’s inaugural publishing roster. In the past six weeks, the organization has released two other books: a series of interviews with 14 master furniture makers and a monograph of the painter and printmaker Robert Kipniss. And in June, it is releasing its first catalogue raisonné — a definitive and comprehensive inventory of an artist’s work. This inventory, priced at $150, is devoted to the sculptor and furniture designer Wendell Castle, whose creations can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Artful Amusement — D.A. Wolf, DAILY PLATE OF CRAZY (Aug 2013)

Do you go to museums? To art galleries? Do you expect to be entertained as if you were at a movie or a theme park?

I haven’t attended an exhibition in some time, much less wandered through an intriguing space, be it a gallery or museum. I’ll offer my usual excuse — no time — but I find it’s a poor one, especially in this circumstance.

If I believe in supporting the arts (and I do), then I need to act on that conviction by seeing art. More importantly, if I believe art is healing, inspiring, consoling, energizing — why wouldn’t I want to partake?

The visual arts provide me a meditative space — stress relief, if you will — that I find in few other activities. At times it’s pure (easy) viewing pleasure. At others, I’m afforded intellectual challenge along with an enjoyable experience.

And I don’t expect it to be explicitly “interactive.”

Can We Open Our Eyes?

The New York Times tackles the issue of art as amusement park or rather, the ways in which our museums are compelled to “activate” their exhibition spaces. In “High Culture Goes Hands-On,” it’s clear to see how our societal slide into “busyness” over thoughtfulness is expressed in our cultural endeavors.

Judith Dobrzynski writes: “…cultural institutions are changing, too, offering more of the kinds of participatory experiences available almost everywhere else. Playwrights now turn theatergoers into participants or let them choose the ending. Botanical gardens are adding skywalks that let visitors traipse through treetops. Museums stage sleepovers in the galleries and dance parties in huge atriums…”

Is there anything wrong in this? I think some of it sounds like fun, don’t you? Why not transform some portion of our highbrow hallowed halls into happenings?

But note … I said … some portion.

Busy? Bothered? Bombarded?

Whether we take the Great Adventures approach to acquainting ourselves with abstract expressionism or some more conventional method, I’d say the appropriate process is a matter of degree. And that’s the dilemma: When is the entertainment factor going too far? When does it hamper rather than enhance the agreeably solitary and leisurely experience of viewing art?

And so we bump into our “busyness” quandary — our need to schedule, to score, to check off our accomplishments without necessarily finding meaning or pleasure in them.

Isn’t this tendency already prevalent in too many areas of American life?

Are we so accustomed to going-going-gone that we don’t know when to say stop, or for that matter — not this, not here, not in this space? Aren’t we bombarded by enough interactive venues as it is, and consequently under-engaged in what is soothing, private, and possibly more profoundly felt?

We’re so invested in staying (seemingly) productive, we schedule and scurry and slide along, convinced we’re “experiencing” and equating that with a big Thumbs Up. But it seems to me that as we do so, we’re thinking less, we’re feeling less, we’re absorbing and retaining less — or certainly less thoroughly, less intensely, less viscerally — as if without the “doing” we’re not certain of our “being.”

Where is the delight that we can hang onto? Where is the savoring?

Why We Need Art: Humanizing, Healing

Art is humanizing and connective. Doesn’t it help us heal as well as providing not to mention pleasure? Doesn’t it recall memories, make us grin, lift us up?

In the wake of my most painful moments, art has always been a source of extraordinary comfort. I could lose myself in color and form, the texture and movement of layers of paint, settling into a place where no words were needed —a t least for a short time. I could forget my troubles, and my distress was lightened.

When possible, as solace or celebration, I view the real thing: modern and contemporary masterpieces displayed in my local museum and occasionally elsewhere. When this isn’t an option, I rely on books or the Internet — not quite the same effect of course, but wondrous all the same.

Doubting the positive impacts of art on emotions? Consider this: “Art Can Be Good For Mental Health” by Michael Friedman, LMSW. He writes: “Art can help a person reach into largely unconscious parts of the mind and experience dimensions of self otherwise buried and voiceless. It can also help a person get a handle on emotions that are, to borrow a word from T.S. Eliot, “undisciplined,” and therefore inarticulate. Through the arts people can find voices to express dimensions of self usually left in silence. And through art, people can shape their own identity. Art is not just self-expression; it is also self-creation.”

Has “Museum” Become a Dirty Word?

A jaunt to the art museum?

It used to be a privilege and a pleasure. These days it seems like a dirty word — a “must do” on the checklist of items when you tour a foreign city or visit a friend across the country.

I remember being startled a few years ago when my teenager asked if our family membership to the art museum was current. He wanted to attend an exhibition with a friend, and naturally, I was delighted. I told him yes, just go, give our name, and pick up two tickets.

But I kick myself that I didn’t bring my children to museums more often, though they frequently joined me in galleries long before I began reviewing art. At the time, on my “off hours,” these were my soul-filling rest stops. My sons have also been surrounded by my own little collection and a sizable art library, so they are, at the very least, visually aware.

And no, a collection doesn’t require a fat wallet (though it doesn’t hurt); it only requires curiosity, educating oneself (even lightly) and training the eye — all reasonably satisfied via the Internet.

How to Interest People in Contemporary Art

As a child, I visited Boston’s many art museums and also the Science Museum, which was more hands on than most, and of course, I loved it. But it was the exception at the time, not the rule. That made it a memorable experience for its distinctiveness. As for the art museums, I would look and absorb, occasionally my mother might explain something, but generally we needed few words. We looked. We experienced. We enjoyed.

As for encouraging interest in contemporary art, or modern art, or more classical periods that are, for some, easier to understand?

What if we ask the viewer what he or she sees? What if we encourage relating emotions to our impressions of art? What if we provide a small amount of information as needed—to guide the viewer in appreciating color and line, composition and materials, and the artist’s process?

What if we propose that it’s okay to smile, to laugh, to enjoy the wit in the artist’s viewpoint? What if we open doors to creativity and interpretation just enough to allow the individual to experience the art as he or she sees fit? What if then, and only then, we suggest explanations of an artist’s intention — or sooner, if asked?

And what if we actually funded the arts programs in our schools?

Why We Need Art? It’s Some Kind of Wonderful…

When I’m fortunate enough to visit New York, I hightail it to the Museum of Modern Art where I set myself down in front of a Willem de Kooning, or I pop by a gallery to enjoy the glyphs and gambols of John Himmelfarb.

In San Francisco, I indulge in Richard Diebenkorn or Arshile Gorky. In Paris it’s Georg Baselitz or Paul Klée at Centre Pompidou, or days among the galleries of the Marais for those who push the boundaries of classification like Fred Deux and Michel Macréau.

These are all artists whose works hold me in their thrall — with quiet, with questions, with raw energy and vitality. For me, this is relaxation, amusement, sanctuary, joy. If you muddle my spaces with “activity” then you ruin the very sacred quality of the experience — viewing and feeling the art itself.

PV 29 (2013), A Moment of Silence (2013), Daemon (2009), Down By The River (2004)

Special thanks to artist, John Himmelfarb, for permission to reproduce his works here. His career spans 40 years of remarkable drawings, prints, paintings, sculpture, murals and installations, held in public and private collections across the US and overseas.

Still Abstract After All These Years: John Himmelfarb — Edward M. Gomez, Art and Antiques (Feb 2013)

Based in Chicago, John Himmelfarb is another artist for whom abstraction’s inherent ambiguity is its own reward. “My interest lies in the pure use of visual language without the baggage of imagery or narrative,” he says. As a result, some of his works appear to be primarily essays in expressive mark-making. Others, semi-abstract, are vigorous formal workouts that start with recognizable subjects — a face, an old camera, a swirling sea of everyday objects — whose shapes the artist reduces, contorts, explodes or obscures in rhythmic compositions or distorts with gusto.

Both of Himmelfarb’s parents were artists. His father was a regionalist painter who had studied at the Art Students’ League in New York; his mother focused on nature and architecture and, after a trip to Asia, produced images based on Arabic writing. “I grew up with books about modern art on the kitchen table,” Himmelfarb says. Jean Dubuffet and Mark Tobey are among the major modernists whose work interests him.

Himmelfarb has also been influenced by anthropology and calligraphy. “I respond to different kinds of mark-making systems,” he says. Like the epic novelists of the 19th century, he feels an urge to tell big stories through his art but also wants it to remain abstract. If that sounds like a conundrum, for Himmelfarb it also proposes an ambiguity-flavored solution. “Stories require settings,” he says, noting that his work may simply be seen as offering “a setting in which something happens.” Tiptoeing on the edge of figuration while driven by — and steeped in — an unshakable abstractionist’s impulse, Himmelfarb’s is an art of imminence and ever-shifting focus.

Juggernaut (2010), Riding High (1982), South Bank (1994)

Blue Motive — unsourced (2012)

John Himmelfarb’s distorted doppelgängers of old trucks are almost painterly, belying their gravitational solidity. There seems to be a celebration of the workaday, the blue-collar, a lack of “fine” aesthetics. The barnacle-like forms, the weightiness, and the encrusted patina all reference an old worn-out vehicle. His work — like a truck that has outlived its use remains obstinately immobile, stubbornly useless. By comparison, the plywood sculpture Blue Motive is light and airy, as if leaving a window open to admit a warm summer breeze carrying the visual pun of the title and materials.

Keep on Truckin’ — Artist Himmelfarb returns to Omaha via new ‘vehicle’ at MAM — Janet L. Farber, The Reader (Oct 2012)

Artists from outside Omaha have always had a presence in the local art scene. They help to keep the artistic landscape varied and lively, enhancing the conversation about how regional artists partake of a national or even international dialogue. Some of these “carpetbaggers” are shown but once, while others become returning favorites.

Among the latter, Chicago-based artist John Himmelfarb has been exhibiting his lively, retro-modernist flavored paintings, prints and drawings in Omaha for so long that he’s no longer thought of as an outsider, but more like a visiting relative who never truly outstays his welcome. It is with anticipation that the nationally recognized artist rolls into Modern Arts Midtown with his latest works in tow: John Himmelfarb: Paintings and Sculpture runs from October 2-27, with an opening event on October 5 from 6-8pm.

Even fans familiar with Himmelfarb’s art will be pleasantly surprised by new works featured in the exhibition. For about the last nine years, Himmelfarb has centered his work around a new motif: the truck. Also driving his creative impulses is a swing to the three dimensional; small and large scale sculptures are additionally highlighted here.

For those frequent travelers in Omaha’s art circles, it’s a given that there are merely one or two degrees of separation between participants. That Himmelfarb’s orbit came to interweave local collectors, Gallery 72, UNO, and the (then) Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery was predestined.

It began with the friendship that his mother-in-law had established as a college student with Omaha native Kop Ramsey, a connection that continued through their adult years and passed over time and equally by chance through their respective daughters. At the time, the young artist Himmelfarb was expanding his out-of-town patron network by showing his work in other people’s homes, and was invited by his friends to bring this experience to Omaha.

After several successful private events in the early 1970s, his hosts introduced him to Bob Rogers, proprietor of Gallery 72, who along with his wife, Roberta, had made it their mission to bring in a variety of national and international contemporary arts to what was then a limited gallery scene. Himmelfarb had his first solo show there in 1979, a heady prelude to his solo debut in New York. He quickly became a favorite and was featured there a dozen times through 2008 before Rogers’ retirement.

He was also introduced early on to Norman Geske, who exercised his affinity for Himmelfarb’s ink drawings with an exhibition at Sheldon. He’s been an artist in residence at UNO and a visiting artist at Joslyn; public works of art can be seen adorning the exteriors of Conestoga Elementary and the Omaha Public Schools Teacher Administrative Center. It seems fair to conclude that anyone who has not seen his work in the area has not been paying attention.

The truck as a motif in the current exhibition is rich in visual, cultural and economic associations. These omnipresent, hulking beasts of burden take on relic-like qualities in Himmelfarb’s art through his characteristically jaunty linear rhythms, bright color palette and lively anthropomorphism.

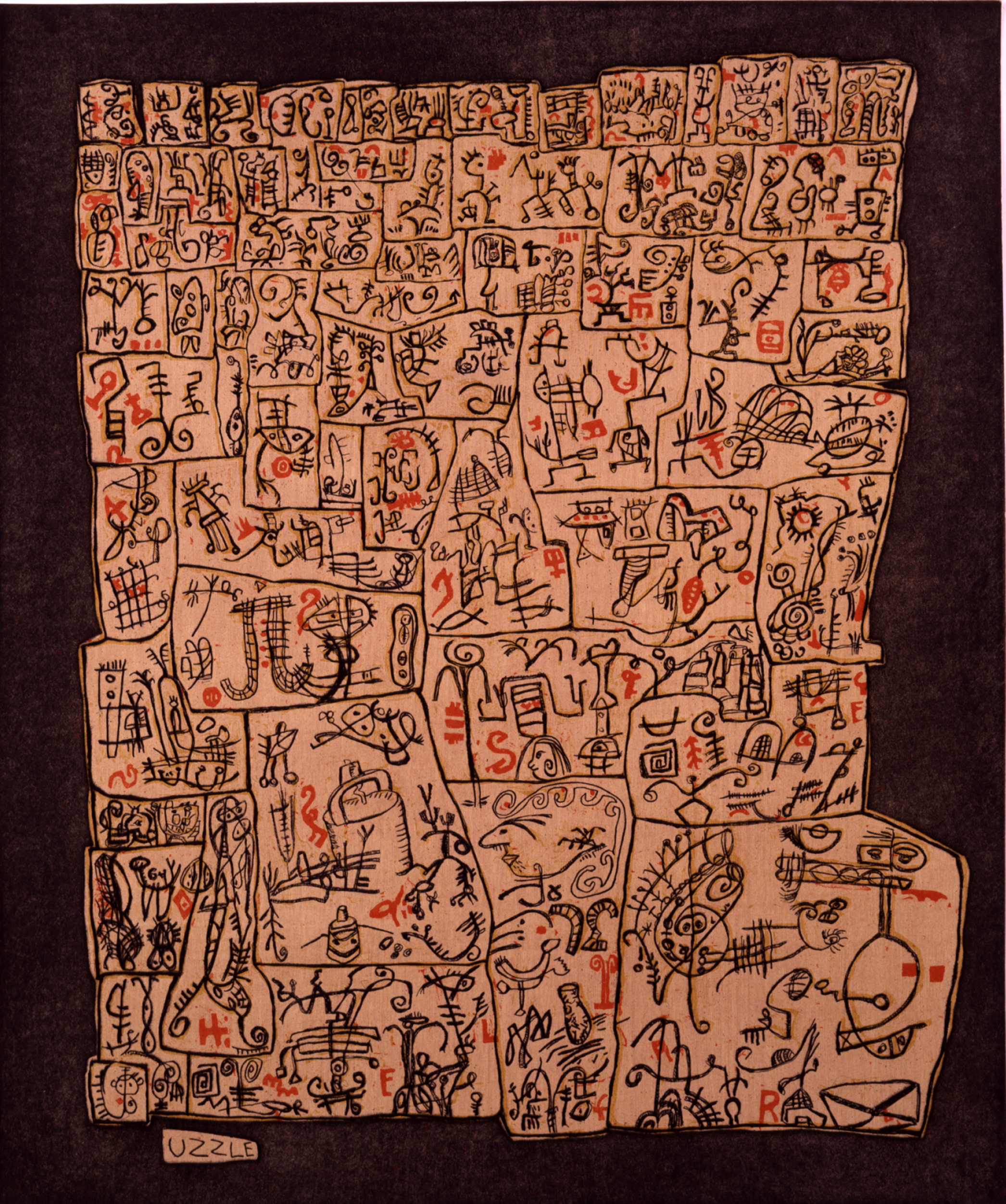

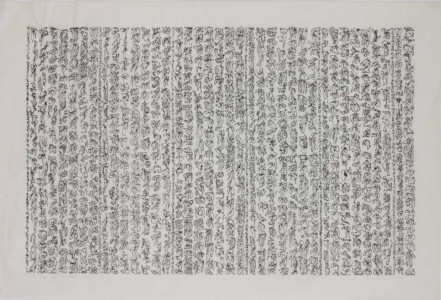

His route to this vehicle was more circuitous, as can be seen in strongly calligraphic drawings such as Say Some Words. This elegant ink on paper has columns of ciphers that hint at a legible text of unknown dialect. It is in fact Himmelfarb’s invented language of gestures and figures, whose rhythms dance delicately across the page. Such works metamorphosed into more hieroglyphic pieces, including the bronze relief Wax Eloquent, in which symbols seem to tell a story; they are Himmelfarb’s Rosetta Stone.

For an artist who works along the edge of abstraction and figuration, this is natural, comfortable territory. Why shouldn’t a distinct abstract form, perhaps in connection with other such shapes, be capable of communicating ideas, information, emotions and the like in the same way as fully representational art? For example, there’s no specific reason that a stop sign must be red and octagonal, but through years of repetition, it is a convention that is understood globally by sight, regardless of any word printed on it. And by inventing and playing with shapes and forms, somehow the truck popped into Himmelfarb’s view and became a recurring icon.

He used the opportunity of an artist’s residency at the Kohler company, the international maker of bath and kitchen fixtures, to cast a series of trucks in bronze. These craggy, lumpy works seem to describe both the molten nature of their casting and the heavy industrial lugs that they represent. Though reasonably small in scale, they are dense and massive and gloriously imperfect. They bear weighty titles, such as Fortitude or Fidelity, all assigned after their making and in response to a sense of the human qualities they communicate.

Lighter, even joyous in spirit, are Himmelfarb’s wood sculptures Blue Motive and The Road to Herron. They are constructions of jigsawed pieces of plywood to which woodcuts or silkscreen prints have been adhered. Almost immediately, they call to mind the wooden toys of childhood and the happiness of play. That they are brightly colored and rendered with an intentionally naive charm makes them even more attractive. And do not miss their big brother, The Road Ahead Leaves a Trail Behind, a large orange work in steel, on the plaza outside Modern Arts Midtown.

Himmelfarb’s paintings are, in a manner related to the Kohler trucks, more expressionistic and, like his drawings, emphasize the movement of line as well as form. Dug In is an energetic exercise in continuous line drawing; deep violet lines of paint fill the blue canvas from edge to edge. The truck is not entirely legible in this tangle of twisted form, but can be recognized by its cab and wheels.

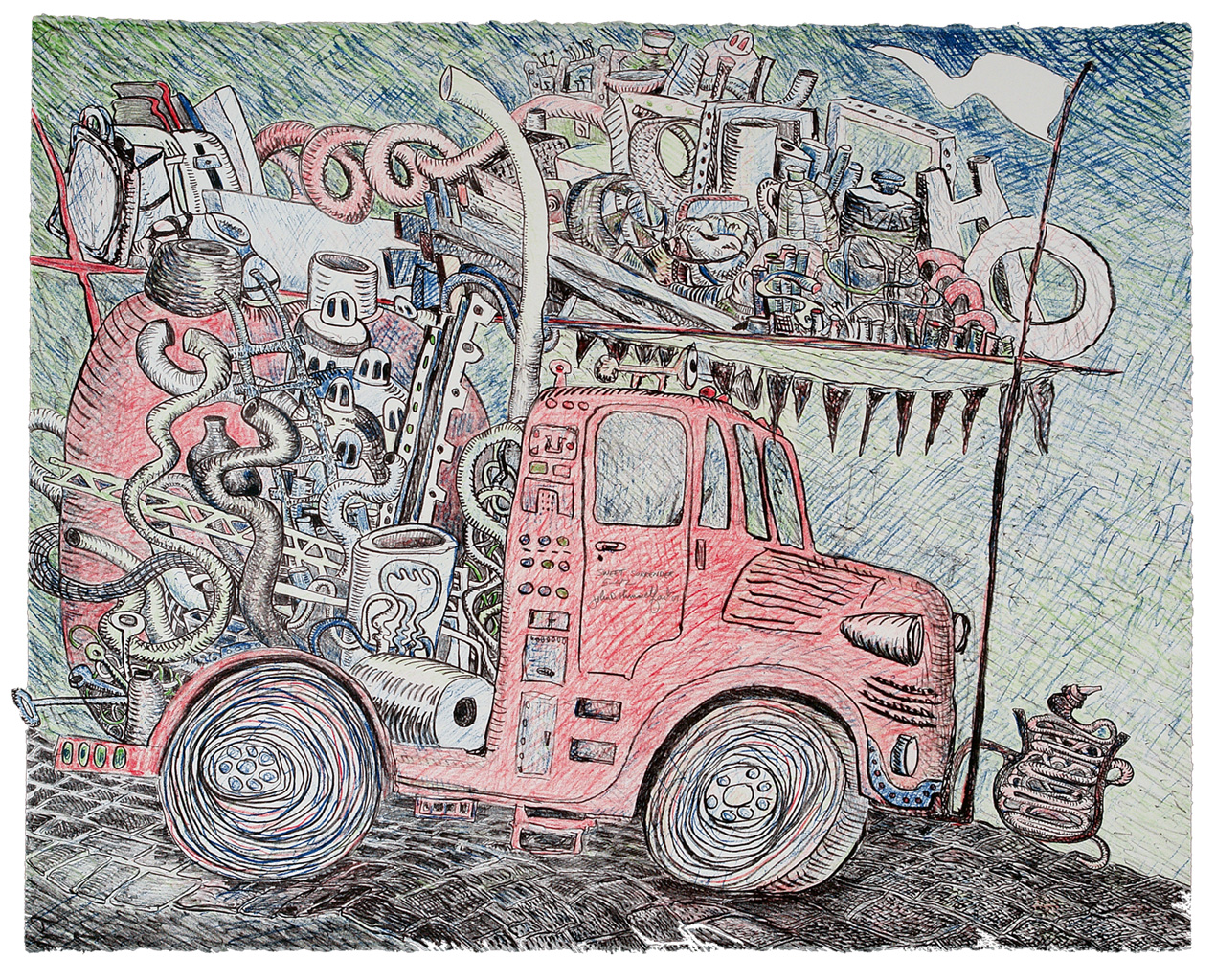

Conversely, Hero is felicitous, with its truck chugging across a pink landscape, with a red and blue mass of stuff springing out of its bed in every direction like a bad hair day. Himmelfarb’s animated drawing and brushwork accentuate the precarious balance of its cargo. It partakes equally of cartoon animation as it does, say, of early twentieth century Fauve painting.

It’s hard to be disconnected from Himmelfarb’s work. It contains imagery that is so familiar and speaks about the ways we work, the materials we use (and discard), and the sturdy motion of labor. It looks back, often nostalgically, at grand old machinery, as well as trying to bring the past into the present by revisiting aspects of Modernism to find the life remaining in its approach to picture making. It’s a journey Himmelfarb is making; if there’s room in the cab, the viewer is welcome to hitch a ride.

Exhibit features artwork built around paper — Adam Testa, Southern Illinoisan, Carbondale, IL (Sep 2012)

A new exhibit at the Southern Illinois Art and Artisans Center showcases artists’ abilities to use an everyday object as a crucial part of their work.

Eighty items from 71 artists using paper as a creative contributing element or foundation are featured in “On and Of Paper,” highlighting selections from the Illinois State Museum Collections. The exhibit includes paintings and drawings, photography, digital art, woodblock, lithographs and etchings and more.

Paper has been used for centuries as a versatile, readily available, and relatively affordable material for the artist. Folded, molded, painted, torn, glued, or otherwise altered, it becomes an element in the creation of a finished piece. Its texture, weave, and color contribute significantly to the final image.

“On and Of Paper” reflects the many artistic uses of paper by historical and contemporary artists. Featured artists include Buzz Spector, John Himmelfarb, Gertrude Abercrombie, Julio de Diego, Misch Kohn, Ellen Lanyon, Robert Lostutter, Bert Menco, Bea Nettles, Hollis Sigler, Julia Thecla, Claire Zeisler, Carolyn Plochmann, Charles Swedlund, Bill Branson and Barbara Crane.

The exhibit remains on display at the gallery, off Interstate 57 exit 77, through January.

John Himmelfarb at Luise Ross Gallery — Stephen Maine, Art Critical (Mar 2010)

The veteran Chicago painter and printmaker John Himmelfarb has recently turned to sculpture in a variety of mediums. Several delightful examples of his foray into the third dimension are now on view in a rousing show entitled “Geared Up,” at Luise Ross Gallery. Himmelfarb’s ostensible subject is that most utilitarian of vehicles, the truck. The choice of motif might seem puzzlingly prosaic but in the hands of this artist, now in his seventh decade, becomes a funny and poignant metaphor for our knack for accumulating emotional baggage — psychic freight — and the increasing unlikelihood, as years go by, of finding a suitable place to dump it.

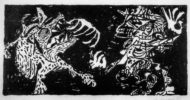

Himmelfarb’s flat work is restlessly graphomaniacal, as a lithograph titled Double Negative (2009) demonstrates. A timeworn but sturdy flatbed truck, its deep wheel wells and streamlined hood of pre-War vintage, is piled absurdly high with not-quite-nameable items that might conceivably include plumbing supplies, inflatable rafts, aircraft parts and/or semiabstract garden sculpture (but that’s just a guess). Graphically simpler, though still plenty convoluted, Drift Ice (2009) is a relief print in jet black and snow white in which the play of shapes takes on narrative and conceptual shades of gray: the rig and its cargo are either falling apart or coalescing, depending on your outlook.

In the exhibition’s namesake, Geared Up (2010), Himmelfarb draws with his jigsaw, summoning from sheets of plywood a repertoire of well-honed shapes and rhythms. Cobbled together with spots of glue and a handful of nails, the piece is a lively heap of interpenetrating planes sitting astride unmistakably tire-like disks and surmounted by a trio of enigmatic protrusions that might be ladders or crane arms. The ad-hoc quality of its formal buoyancy has an unlikely elegance: Red Grooms meets Isamu Noguchi.

The beautiful, somber Mesa (2008), a three-and-a-half-foot-long bronze, is a hybrid of the eroded landform the work’s title indicates and a loaded lorry as if it broke down while making a wide right turn, lost a tire or two, and merged with the geography. The windshield and grille take on a physiognomical cast as it is easy to read them as wide, hollow eyes and gritted teeth.

Himmelfarb’s work has little to do with the spirit of the convoy, that fluid confederation of cross-country tractor-trailer drivers that became a sociological phenomenon and pop-cultural touchstone (“Good buddy, put the hammer down!”) by making Middle America aware, in the mid-1970s, of the existence of subcultures in its midst. It’s more existentialist and individualist than that, as in the 16-inch-long Fortitude (2010), a smaller truck inexplicably equipped with a distinctly simian front end, a huge gearlike tire, tanks and canisters galore, and a number of mysterious protuberances such as a wing or huge comb on the front fender, possibly deriving from outmoded or reinvented agricultural equipment. and other and possibly outmoded farm implements what looks like a reinvention of the ladder.

The spikey Knowledge (2009) looks at first like a collection of barnacle-encrusted boomerangs and banana peels. It is set upon a plinth that brings it to eye level, enabling the viewer to get to know the nooks and crannies. In the manner of the sculptor William Tucker, the work is abstract from a great many angles; only its vestigial tires and bonnet, seen from three-quarter view, give away its vehicular origins. Visitors to the gallery should be sure not to miss Lander (2008), displayed in a back room. It is a small and tidy, slab-built ceramic work with a beautiful polychrome glaze keyed to dark gray and neutralized pastel colors.

Back in the 1980s, Himmelfarb did a series of drawings called “Boatman” in which mounds of prosaic junk, accoutrements of the everyday — stepladders, cigar boxes and the like — are piled high in a raft, threatening to sink it, and the anxious fellow piloting it. Just as his overburdened rafts struggle to remain afloat, Himmelfarb’s straining rigs somehow keep a-rolling. Perseverance (2006) is an eleven-foot-long painting keyed to orange-red, black, and pale blue-green. Through the loose, exuberant paint-handling the viewer discerns a barreling semi nearly filling the frame, filled to bursting with tubs, spools, coils and cartons of unnameable, unknowable stuff. The truck is fully loaded, like the brush it was painted with. When art is so witty, self-aware and bemused emerges from an artist’s accumulated experience, that load proves to have been worth schlepping, after all.

Luise Ross Gallery Presents John Himmelfarb: Geared Up — BWW News Desk (Apr 2010)

In the past, John Himmelfarb — the Chicago born, bred and based working artist — has occasionally incorporated truck imagery in his work, usually in an ancillary role, or as a single character in larger, more complicated pieces. In more recent years, he has been using the image of a truck as the central organizing principle in his paintings, drawings, prints, and now in sculpture. The latter comprise the predominate work in this exhibition at Luise Ross Gallery.

In Himmelfarb’s world — somewhere between abstraction and figuration — the three bronzes, one large plywood sculpture, and the one wall-filling painting in the show are clearly identifiable as trucks. Rather rickety and tired from countless trips and loads, perhaps, but Himmelfarb captures the very essence of trucks. And with artistic wit and inventiveness in the line and form of his depiction, the truck imagery morphs into almost human physical attributes and attitudes in the viewer’s imagination. The artist’s titles for some of the pieces — Fortitude, Knowledge, Perseverance — suggest human virtues dating to the Aristotelian and Platonic tradition, and are clues to his intended anthropomorphism.

And what do trucks do? They carry stuff, and Himmelfarb’s are loaded. Perhaps a truck aficionado other than the artist will recognize a crane arm at rest, or the suggestion of a crank shaft, but most viewers will be content to categorize the cargo as a collection of forms suggestive of impedimenta, of “stuff” acquired and accumulated over time and experience, just in case. And for the Heads out there, it’s OK to assume that Himmelfarb’s wonderful work in this exhibition is a fitting nod of homage to “Truckin’.”

Review: John Himmelfarb / Finestra Art Space | RECOMMENDED — Dan Gunn, Art Editor, New City Art — Visual Art Culture of Chicago and Beyond (Sep 2009)

For an artist whose name roughly translates from the German as “the color of the heavens,” there isn’t much color in John Himmelfarb’s exhibition at Finestra Art Space. Himmelfarb’s mostly black-and-white drawings are primarily about texture, both of the textual and implied variety. The major work in the show is a large ink drawing on paper titled Protest. The work is comprised of vertical rows of darkly inked quasi-symbolic, pictographic marks. The gestures in Himmelfarb’s “writing without words” are a series of improvised calligraphic strokes that never rise to the level of legibility. Instead, half-formed images appear and disappear as one reads up and down the row. Other smaller works on paper accompany the much larger Protest. In the etchings Plot Outline and Night Life, layers of delicate lines lay in piles contained within sectioned grids. Each square of the grid is darkened by an accumulation of meandering lines. Taken together they resemble dimly lit waves or folds of fabric. The imagery in the works hearkens back to the beginnings of modernism and its embrace of “primitive” symbol systems. As well-crafted and thought-out as these works are, they would be better served if Himmelfarb’s historical influences were mitigated by some contemporary element. There simply isn’t much necessity nowadays for an illegible protest, especially one so informed by the past.

Chicago artist showing works at Carthage gallery — Bill Robbins, Kenosha News, Kenosha, WI (Oct 2009)

Trucks a popular theme for John Himmelfarb

Trucks have rolled into an art gallery at Carthage College — in an aesthetic sense.

Paintings, sculptures, and vessels by acclaimed Chicago artist John Himmelfarb — who has an abiding passion for trucks — are on display in the college’s H.F. Johnson Gallery through Oct. 17.

Fanciful and abstract renditions of tow trucks, firetrucks and pickup trucks are common themes in Himmelfarb’s works, said gallery director and Carthage art professor Diane Levesque.

Among Himmelfarb’s styles are hieroglyphic-type paintings featuring images that also appear in his vessels and sculptures.

“The paintings are very simple, with a basic black background and organic shapes on top of that,” Levesque said.

“Within those organic shapes are iconic, almost hieroglyphic images. In some of them you can trucks, human figures and animals suggested.”

Trucks navigate their way into Himmelfarb’s paintings and metal sculptures, some of which are in the shape of old vehicles that give the appearance of decades at the bottom of the sea.

Their rough, bulging textures make them look as if they are covered by coral, like a long-sunken ship.

In contrast to the rigidly defined iconic paintings, Himmelfarb also enjoys letting go and creating riotously colored and densely configured paintings that are almost cartoonish.

And, naturally, many have trucks tooling through them.

When the University of Chicago library switched from card-catalogues to a data-base system, Himmelfarb bought several huge oak cabinets containing index cards listing books.

“The cards suggested tantalizing subject matter,” Levesque said.

Himmelfarb began randomly picking cards out and drawing on them. That’s where the idea for this show’s name came from: “Circulating Library: Selected Recent Works by John Himmelfarb,” Levesque said.

Himmelfarb occasionally uses the tiny illustrations on the cards as a basis for larger artwork such as paintings.

Over the past four decades, Himmelfarb has built a complex and compelling set of approaches to creating abstract works that are outside conventional stylistic impulses, Levesque said.

“The complex vision that unfolds is a rich dialogue of color and themes that together form a ‘library’ of resonant images,” she said.

Himmelfarb counts among his influences Jackson Pollock, Pierre Alechinsky and Jean Dubuffet.

He has shown his work in nearly 90 solo presentations and in major museum collections throughout the United States and overseas.

Those include the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum in London, Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Milwaukee Art Museum.

His paintings have been likened to calligraphy and include images that could be figurative or abstract — or a combination of both, said Levesque, who co-curated the show with Geoffrey Bates. He is the director of the Nathan Manilow Sculpture Park at Governors State University in University Park, Ill.

PHOTO CAPTIONS:

John Himmelfarb’s “Deep Green Sea” is one of the pieces on display at Carthage College.

John Himmelfarb’s “Hope“

Artist’s truck sculpture finds home at Lincoln Industries — Micah Mertes, Lincoln Journal Star, Lincoln, NE (Jun 2009)

Head out of town west on Rosa Parks Way and look left, and you’ll spot a curious bit of not-quite-fire-engine red.

Sitting out on the green of the Lincoln Industries campus is a truly unique work, a 1949 International KB-1 pickup truck converted to sanguine sculpture. The piece, aptly titled Conversion, has shovels, picks, pitchforks and other pointy what-have-yous poking out of the truck’s old frame.

In the truck, there’s an 8mm film projector and several 8mm prints of old Mack Sennett comedies. There’s a drop-down screen outside the windshield for any passenger who gets a hankering for some golden-age slapstick.

The work’s artist, John Himmelfarb of Chicago, said he got the idea for the piece when he’d spot utility vehicles piled as high as possible with stuff. Sometimes all that junk would have this gorgeous composition to it. Using found objects, buckets, trash cans and old scrap, Himmelfarb went looking for beauty in the arrangement of old, mangled metal.

The symbol of trucks has popped up in Himmelfarb’s work for the past 30 years. “It’s something left over from childhood,” he said. “I’ve just always had a fascination with them.” There’s just something about them that’s so easy to anthropomorphize, he said. They’ve got a personality, a soul. “It’s kind of like how some kids relate to Transformers,” he said. “I tend to see trucks as characters.”

Marc LeBaron, chairman and CEO of Lincoln Industries, and his wife, Kathy, bought the piece, so Himmelfarb brought “Conversion” to Lincoln early last week. Here, he gave it a few final touches before heading back to Chicago, where he’ll get back to work on his next projects.

And many of them will involve trucks.

John Himmelfarb at Flatfile Gallery — Mike Pocius, art critic, Lumpen Magazine, vol. 17, iss. 1 (Jan 2008)

The work of John Himmelfarb has a frank openness and approachability that will engage the most inflexible audience. His colors and stroke disarm the please centers and wit grips the intellect. The abstract paintings capture us in a web of entanglements. The paintings display a youthful agility which can be disconcerting to some, with its carefree attitude, and conceal his deft cleverness and graphic abilities. Some of his works, particularly, his sculpture and tapestries feature a kind of invented alphabet akin to Chinese calligraphy imbued with his own personal symbolism. John also does loose figurative work extremely penurious of line and detail. The paintings feature toy-like vehicles quick of shape and execution, anchored to a most abstracted background. His style and temperament at times reminds one of Raoui Dufy, but still an original of his own time and design.

John Himmelfarb at Luise Ross Gallery — Jonathan Goodman, Art in America (Apr 2008)

In his tenth New York show, including works of three decades, Chicago artist John Himmelfarb showcased what he does so well: schematic mark-making that suggests different image languages and systems of thought. Indeed, the show’s title, “John Himmelfarb: Ideographic Sequence,” prepared the viewer for a series of highly abstracted visual idioms whose intelligence constitutes a large part of their charm. The results of his investigations into calligraphic abstraction are remarkably varied, both imagistically and in terms of materials — Himmelfarb works with pencil, acrylic and ink, as well as printmaking and sculpting in aluminum and bronze. And while the results do not necessarily look alike, it is clear that Himmelfarb has a unifying theme, in which the ideograms demand to be read as a language even as they are experienced as pictures.

In the acrylic-on-linen Gooze on Oakley (1995), three large ideographs, more or less resembling Chinese characters, are painted in gray outlined with bright orange. The background is a crowded mélange of blue and black abstract strokes, which may also be seen through the small openings in the ideographs themselves. Treading a line between abstraction and figuration, the three forms might easily be read as two figures and a head. The acrylic-on-canvas Inland Romance: Getting Through the City (2004) consists of black gestures on top of lighter colors — orange and slate blue predominate. Here the influence of Abstract Expressionism comes into view, as well as the schematic vernacular of German artist A.R. Penck, with whom Himmelfarb shares a restless intelligence if not stylistic symmetry. These two paintings underscore Himmelfarb’s search for a vocabulary that would do justice to urban experience in all its complexity and drive.

Some of the more overtly calligraphic pieces, such as the ink-on-paper works Townsend (Roslyn Place), of 2002, and 5/30/79 (1979), resonate as exquisite studies of gesture; in 5/30/79 he has written his marks in horizontal rows, plainly establishing the existence of a text, no matter how abstract its language. The relatively large (50 by 34 inches) acrylic-on-canvas Poem of Prospero (1998) plays with what might be seen as Korean or Chinese seal script; large ideographs are arranged in rough rows over a field of busier brushstrokes. Finally, the small sculpture Proposal (10 by 10½ inches), from 2003, represents in bronze what might be two pictographs joined in the middle or, read more as an image, one person proposing to another, seemingly on bended knee. The ambiguity of the piece’s formal relations, at once figurative and abstract, gives a remarkable allure.

Art Business: Building Your Own Printing Press — Daniel Grant, ArtistsNetwork.com (Sep 2008)

Painter John Himmelfarb had been making prints for almost 40 years, but it wasn’t until Hudson Hills Press produced a catalogue raisonné of those prints in 2006 that the artist realized prints were an essential part of his career, generating 10 percent of his income selling art. A year after the catalogue was published, Himmelfarb bought a $17,000, 7′-x-4′ etching press that occupies a large portion of his Chicago studio.

“Now, when I have an idea or inspiration, I don’t need to rent a shop or wait to get invited by a publisher or university to do a print edition,” he says. He no longer has to pay $300 or more each day and be “creative on demand” during shop hours. “I’m on my own turf, and I can control the process more,” Himmelfarb explains. If sales continue as they have in the past, he figures, the printing press will pay for itself in one year. In the 1990s Chicago artist Tony Fitzpatrick bought a printing press for a few thousand dollars, and the cost was recouped within three months.

Sales of artist printing presses have increased sharply in the last decade, and a variety of factors are driving the move. There are fewer fine-art print studios, and those that remain are more expensive. “Many artists want to make prints in their own studios, rather than traveling somewhere to do it,” says Amber Millen, a saleswoman for Ettan Press Company, in La Jolla, California. Additionally, printmaking used to be associated with hazardous chemicals, but the new generation of materials features water-based inks and nontoxic solvents that make home-studio use less worrisome. For all artists, control is a major consideration.

Because most artists don’t want to deal with the massive presses used by commercial print publishers, manufacturers are producing lighter, less expensive machines. “I started out as a printmaker and engineer,” says Mel Whelan, the president of Whelan Press, a printing-press manufacturer in Santa Fe, “and I got tired of moving 1,800-pound presses through windows and doors.” Putting his engineering know-how to work, he developed a line of smaller presses that create full-size prints (22″ x 30″) and range from under 100 pounds ($1,495) to 396 pounds ($6,000). Whelan sells approximately 200 printing presses per year, and about half of those sales are to artists.

Artists represent only about 25 percent of the customer base of Takach Press Corporation, a manufacturer in Albuquerque, New Mexico, but that is up about 50 percent over the past decade, according to salesman David Takach Jr. The bulk of Takach’s sales are large costly models to commercial printers and university print studios, but the company also makes smaller, lighter machines, such as a 250-pound press (18″ x 36″ and $3,875) that is a favorite of artists.

Dean Clark, the president of Printmakers Machine Company and Graphic Chemical & Ink Company, both based in Villa Park, Illinois, says his printing-press sales to individuals have also increased significantly. Many buyers make their purchases online, ordering tabletop and small table presses, the most popular of which weigh 55 pounds (9″ x 18″ for $675) and 90 pounds (12″ x 24″ for $1,405), as well as larger models weighing 270 pounds (18″ x 48″ for $2,840) and 550 pounds (27″ x 48″ for $4,400).