Meet John Himmelfarb in Heart of Chicago — VoyageChicago (May 2018)

Today we’d like to introduce you to John Himmelfarb.

Thanks for sharing your story with us John. So, let’s start at the beginning and we can move on from there.

I decided I wanted to become an artist when I was a junior in college and began exhibiting my work in public in 1968. After college, I sublet some studio space in Pilsen on Halsted near 18th, then bought a building in 1971, on 19th and Peoria. I gradually developed a national following through exhibitions and travel, but mostly kept my studio in that area until 1991, when I bought an old department store building in Heart of Chicago. At first, most of my work was on paper, but gradually, painting became a bigger part of my work. I found a very good dealer to show my work in New York and had other galleries that showed my work in Chicago, Milwaukee, Omaha and sometimes other places.

In 2007, I was invited to go to the Kohler cast iron foundry as part of their Art in Industry program and learned I could work in metal. At that point, I started making sculpture as well as flat work. I started using the abstract image of a truck in much of my work, and after making some smaller truck sculptures, got the idea to use real trucks that drive with salvaged metal welded together to make the sculptures. I was inspired by the shapes and colors of the scrapper trucks that came by my studio every day.

Today, my clients are a mix of individual collectors, corporations, and museums. I don’t have any walk-in retail sales. Everything is done by appointment or online.

Has it been a smooth road?

Looking back, it looks like a steady progression, but in reality, it was often very difficult to keep the business going and also to keep making better work. The ups and downs of the economy hit artists very hard, as art is the first thing people stop buying when they are concerned about the financial situation, and it’s the last thing they resume buying after the economy recovers. My strategy has always been to keep a very low overhead, but even so, I’ve made some mistakes, like buying new equipment or hiring more help just before a downturn.

Juggling the studio along with marriage and raising kids has always been exciting, even if a challenge at times. When I began, I had no idea how much travel would be involved in this kind of work. I’ve even exhibited and worked abroad once in a while. I had a show in a museum in Korea in the 1990s, and last year I was invited to do some work in Venice, Italy.

Today, my work is in museum and private collections throughout the country and I’ve benefited from the long recovery we are in now.

So, as you know, we’re impressed with John Himmelfarb — tell our readers more, for example, what you’re most proud of as a company and what sets you apart from others.

I make things I want to make and then hope to find someone who wants to buy them. This is the opposite of the usual business model of finding what people want and then making it.

Sometimes, I’m asked to make something for a specific site. I made two 15′ by 20′ paintings for the airport in Boston, for instance, and also made a ceramic tile mural for the Pink Line stop at Kedzie. These kinds of projects are high pressure but rewarding.

I can’t say that I’m proud of my company, it’s just what I do and I’ve had help from so many people who have taught me about printmaking, welding, and many other techniques. But I’m pleased that my work is well accepted and that I am able to continue to learn how to use new methods, including computers, to make my work.

I have a very personal style, so generally, I think that the individuality of my work is what sets me apart from other artists.

John Himmelfarb: Trucks — Sioux City Art Center, Sioux City, IA (2016)

Chicago artist John Himmelfarb has been making art for nearly fifty years. His artworks have been exhibited throughout the world and collected by many prominent museums including the Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC. During most of his long, successful career, John has created paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures that have depicted subjects other than trucks. Yet, since 2003, artworks that feature an image of a truck have become his focus.

What he was working on from the late 1960s until 2003 cannot be easily categorized. John has always kept abreast of what other contemporary artists were doing and has regularly found inspiration in the art of others. But his knowledge and inspirations are much more personal than they are about keeping up with trends in the art world. Among the many recurring themes and ideas in or behind John’s work have been industrial and rural landscapes, human relationships, the mystery and beauty of written languages, and literary and musical references.

Taking a step back from that list of themes and ideas we can see that it encompasses a rather thorough list of what any of us might experience during our lives: places, people, and communication. While many artists focus their efforts on exploring a particular style or material or subject, John has focused his efforts on undertaking an expressive analysis of his personal experiences as they occur. Stated more simply, he waits for interesting things to happen; when they do, he digs into them by painting, drawing, printing, and sculpting as a way for him to find out why those things are interesting to him. In the process, he has created an enormous and dynamic body of work that is unified by the energy John puts into his art. Whatever topic or idea that inspires him to create, we as viewers can see clearly that he was excited by the entire process of making the artwork.

The ideas that have inspired John to make art are consistent in important ways. Our physical environment, relationships, and methods of communication define who we are and how we live. In John’s art, these things are presented with intensity and originality. Things that at first glance seem clear and recognizable turn out to represent nothing but visions from John’s imagination. Things that appear to be chaotic and abstract might conceal recognizable objects. This sense that differences can co-exist—the strange and the familiar, order and disorder—can be found throughout his work.

But trucks?

Why now and what took so long? Why would an artist whose work has been exhibited and collected by major art institutions around the world, shift gears into trucks?

Though John’s artworks are often responses to recent experiences, trucks as a subject in his work came about indirectly. The artistic response was not to trucks themselves, but to a painting by Jean Dubuffet he had seen during a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago in 2003. The impact of the painting was so strong on John that when he first returned to his studio, he let his memory of the Dubuffet painting guide his work. In his retelling:

“l immediately went back to my studio, mixed up some blues and greens (as I recalled them from the Dubuffet), and laid down a patchwork of color swatches of no particular distinction. Over that I began to draw with a liquid black paint, using a thinner brush more suitable for drawing.

“As usual, I had no particular image in mind. I began on the right side with my industrial forms. The result looked like a crane, and I stopped far short of covering the entire plane with this pattern. It wasn’t enough, so I recommenced drawing beneath the boom of the crane. The truck that emerged delighted as much as it surprised me. I felt an immediate visceral connection.”

The “visceral connection” has continued since that moment in 2003. As John indicates in the above quote, the truck came about as an extension of the crane. The crane and other pieces of urban, industrial equipment had begun finding their way into work he had been creating for his Inland Romance series. This series featured bold, abstracted lines and shapes that were inspired by the roads, buildings, and industrial machinery of Chicago and the Midwest. The shapes of trucks, literally and figuratively, represented a move beyond urban architecture toward something more universally experienced. And by 2005, trucks made regular appearances in his paintings and drawings. The more he worked on them, the more he realized that they were capable of imparting a broader message than one of basic utility.

In 2007 John was invited to participate in a three-month residency at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center Arts/Industry program in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. This prestigious program gave him the chance to create sculptures for the first time in any serious, sustained period. He made a series of truck sculptures in wax and plasticene to create sand molds. These were used to create cast sculptures in iron, brass, and bronze, ranging widely in size.

While the subject of John’s works is trucks, it really represents a very specific kind of truck. Like many people, when he pictures trucks in his mind he goes back to his childhood memories of what a truck looks like. In his case that means work trucks that date from the late 1940s and early 1950s. John’s trucks are the tough, powerful vehicles that were in action as the country emerged from the Second World War and began a period of unprecedented growth. The type of truck that inspires him was designed for strength rather than beauty, a no-frills machine for doing a vital job.

This kind of honest dedication to its unsung purpose has often led John to assign titles to the artworks that reflect the value and dignity of the trucks. Dedication, Hero, Honor, Loyalty, and other similar titles tell us that we are looking at more than representations of trucks. We are looking at character. John has stated that the artworks in this series “are not about trucks but about us, our histories. skills and coping mechanisms, ambitions, and character.”

John’s interest in the truck’s sense of character and history led him to his next big step. In 2008 he acquired a 1949 International Harvester KB-I truck. Then, he crammed a host of steel barrels, tools, pipes, and other things, and covered all of the steel of the truck and its additions in bright red paint. John titled the painted sculpture Conversion, and he has since created additional drivable sculptures using work trucks from that time period, including Galatea, Remains, KB-3, and the work on display at the Sioux City Art Center, Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain.

Penelope Awaiting Her Chamberlain began life as a 1946 Chevrolet farm truck. After many welded additions to her cargo area and roof, she emerged as a drivable sculpture in 2013. “Penelope” in Greek mythology refers to wife of Odysseus, who remains faithful to her husband while he is away for twenty years fighting in the Trojan War. In John’s sculpture, rather than awaiting Odysseus, Penelope awaits Chamberlain, referring to artist John Chamberlain (1927- 2011). Chamberlain, who also grew up in Chicago, was best known for transforming old car parts into modernist sculptures.

Like the opposites contained within John’s earlier artworks, Penelope is familiar and strange, functional and artistic, industrial and whimsical and unexpectedly beautiful. It is John’s ability to give us something unexpected from something so common. The truck shifts from its purely industrial function to become a merging of forms and colors that have been determined both by its original manufacturing design and by John’s artistic design. In doing this, John celebrates our century-old appreciation of American trucks, as well as the equally long artistic tradition of converting factory-made materials into artworks.

Truck Route: the Recent Odyssey of Artist John Himmelfarb — Janet L. Farber, Trucks: Recent Works by John Himmelfarb, New York: The Artists Book Foundation, p. 26–64 (2014)

An artist’s career is a journey. It takes place over time, in any number of physical, aesthetic, and motivational spaces. It is most often traced through the development of an individual’s approach to concept and content, to medium and method. Like sleuths, those following its path look for clues of continuity, relishing works that tell us a little about their past while anticipating future directions. Fortunately, John Himmelfarb has hopped on a truck for the most recent part of his personal odyssey and left tire tracks behind.

Looking at the stylistic trajectory of Himmelfarb’s creative life, we encounter an artist intrigued with the good fortune of being born in 1946, with the modern era nearly complete in rear view. There he found a rich heritage of fearless experimentation: The sun-filled pleinairisme of the impressionists. The unblended color of the pointillists. The gaudy non-naturalistic pigments of the fauves. The shattered picture planes and bricolage of the cubists. The dynamics of futurism and its metropolitan fervor. The alliance of abstraction and modern materials in constructivism. The evocative dreams and subconscious thought in surrealism. The emphatically unschooled, child-inspired art of CoBrA and art brut. The rejection of traditional field/ground relationships and the limitless nonobjectivity of abstract expressionism. For Himmelfarb, this legacy was not one to dismiss or flee from but to mine like a treasure trove for its relevance and possibilities.

The result has been an oeuvre that moves easily between abstraction and figuration, between subject and symbol, between the general and the specific, between figure and ground. Himmelfarb’s own approach to modernism is not that of the methodical scholar or devoted connoisseur, having never studied art history formally, but of the enlightened traveler whose encounters with the works of past masters — in museums, galleries, and publications — registers emotionally and viscerally. To shrug them off would be to deny an inherited visual culture that is part of his artistic genetic code.

Himmelfarb explores tensions between past and present in his art, with a kind of retro-modernist vibe developed across multiyear cycles of thematic inquiry. Among these are land- and cityscapes, letterform and map works, narrative puzzle pieces and figurative subjects. He employs forms ancient and contemporary, expressing emotions that are personal and shared, and reveling in the possibilities of mark-making. He also moves fluidly through mediums, including painting, lithography, etching, silkscreen, and drawing in ink or pencil, with a decided preference for linear techniques. Over the last ten years in particular, the artist has focused his studio practice on the many directions he can take utilizing the isolated image of the truck.

Himmelfarb’s muse manifests itself in distinctive forms. His trucks are usually vintage, somewhere between timeworn and timeless. They are not precise renderings of specific machines, but are broadly conceived. They reveal power through the size of their cargo or heft of their machinery. They are thoroughly utilitarian, doing the tough jobs of logging, digging, mixing, lifting, hauling, and towing. They are part of an apparatus of life, but whether their job is to build something up or tear it down is left intentionally ambiguous.

Most importantly, the trucks are imbued with character. They are lively and anthropomorphic, and Himmelfarb often titles his works according to the attitude a finished composition seems to display. They come from a memory bank imprinted with childhood stories and days spent with sandbox toys. They embody skills of building and creating. They also reflect the cycle of items consumed and discarded, of burdens that are material and psychological.

As subjects drawn from the iconic history of American transportation, Himmelfarb’s trucks are categorically unusual. They have a work ethic, but are not pickups — those idiomatic, horsepower-laden extensions of cowboy mythos and frontier spirit. They do not come from classic auto territory; they do not exude muscle or speed or sex. They are a bit baroque yet have no kin among art cars, magic buses, embellished food trucks, or tricked-out lowriders. They have rhythm and motion, but they are not racecars or sleek fleet semis. Himmelfarb’s trucks are clunky and work-worn for sure, but still laboring hard.

As art objects, these truck-themed works are also singular among those artists who have incorporated vehicles into their métier. There is no pop-minded conflation of midcentury consumerism and car culture (James Rosenquist). Its anthropomorphism is divined through the truck image rather than using it as a conceit for polished photo-realistic formalism (Robert Bechtle). The mood is energetic and often light, not existential (Ed Kienholz) or otherworldly (Peter Cain). Himmelfarb’s closest connection in this vein is with the sculpture of John Chamberlain, who found a joy in the colorful, twisted metal of auto bodies, fins and fenders, adapting his rescued materials into exuberant, writhing abstractions like bouquets of brushstrokes.

More fitting comparisons may be found among artists plying other themes, especially those for whom humor is an instrument for broad description. Himmelfarb often mentions a kinship he feels with the work of Philip Guston, whose comics-styled paintings featured wry and at times cynical images inspired by the prevailing social climate. Carroll Dunham works in a similar graphic spirit where modernism meets Sunday cartoons, creating curious narratives inhabited by fetishized images of men and women. Yet, the tenor of Himmelfarb’s art tends to be gentler, having something in common with the exaggerated cornpone of Red Grooms’s Americana. In many ways, his nearest ally may be Joe Zucker, whose 1970s history paintings of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin or paddle-wheel boats were filled with a peculiar postcard charm while, with their quirky, paint-soaked cotton ball construction, taking full aim at the methods and rhetoric of contemporary abstraction. In the comfortable and natural appeal of the truck, Himmelfarb found the perfect mechanism with which to shift through changing gears of content, expression, and design.

The truck motif crept into Himmelfarb’s early work in a gradual, unintentional way. Then, as now, the artist preferred to fill his planar space with an accumulation of images and forms, an affinity he ascribes in part to the scattered aggregations in the bright, cosmic Pedazos del Mundo paintings of Robert Neuman, an instructor of his at Harvard. Compared to Himmelfarb’s current emphasis on the formal possibilities generated by a single figure, these earlier works were busy and expansive. The urban-themed Crane Mountain (1971, pl. 1) depicts an electromagnetic crane dwarfed by what the artist calls “a landfill gone wild.” Similarly, trucks and equipment appeared along with bridges, train tracks, and other components of transportation hubbub as aspects of teeming city life that filled every corner of many compositions of the 1970s. As evidenced in the aerial views of such works as Filming of Sunny Days (1974, pl. 2), Himmelfarb’s approach read like an automatic or freely associative form of futurism or purism, celebrating the vibrancy and fast pace of metropolitan life in the new industrial age.

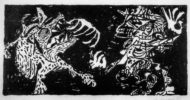

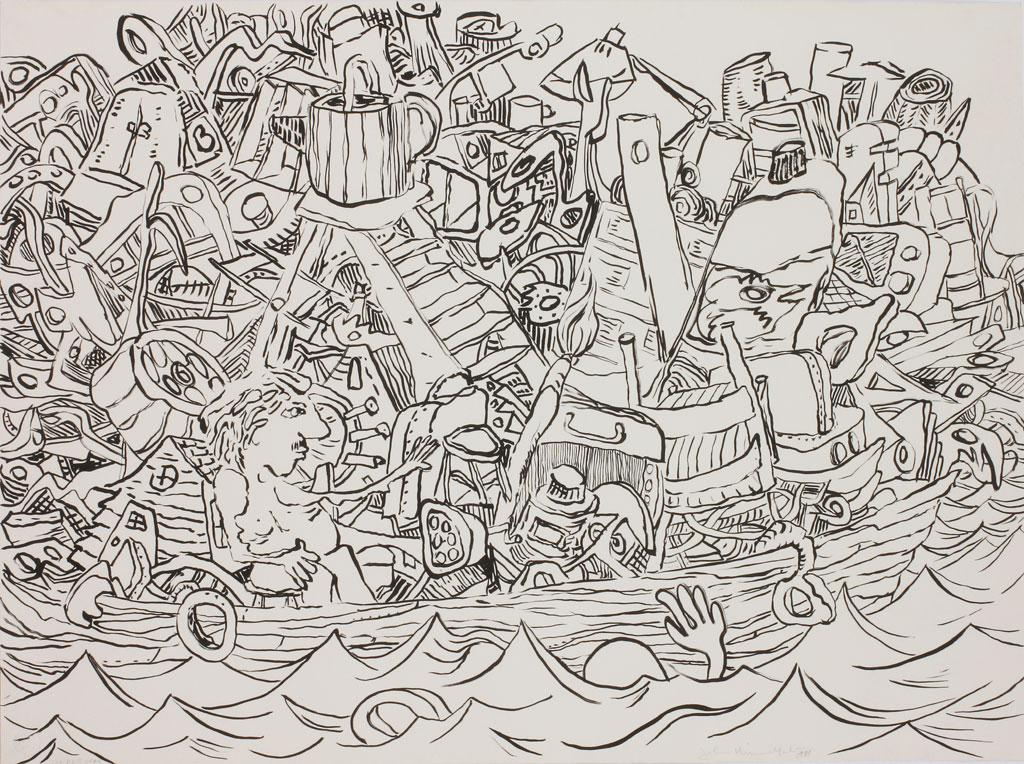

Another precedent might be found in Himmelfarb’s series of Boatman images (pl. 3), realized in black-and-white paintings and prints in 1982. In these scenes, an overladen vessel is adrift in choppy waters, its towering cargo threatening to swamp the small craft. It and its helmsman are truly “at sea,” endangered by the paraphernalia he persists in carrying with him through life’s voyage. These scenes are delightful updates of the Northern Renaissance theme of the “ship of fools,” as codified by Albrecht Dürer and Hieronymus Bosch, widely understood as satiric allegories of human folly, of souls adrift in search of a fool’s paradise. With perhaps a twentieth-century overlay of materialistic “can’t take it with you” values, Himmelfarb has shifted the compositional accumulations in his works to the suggestion of portable burdens that later transpose into the lumbering freight of his haulers.

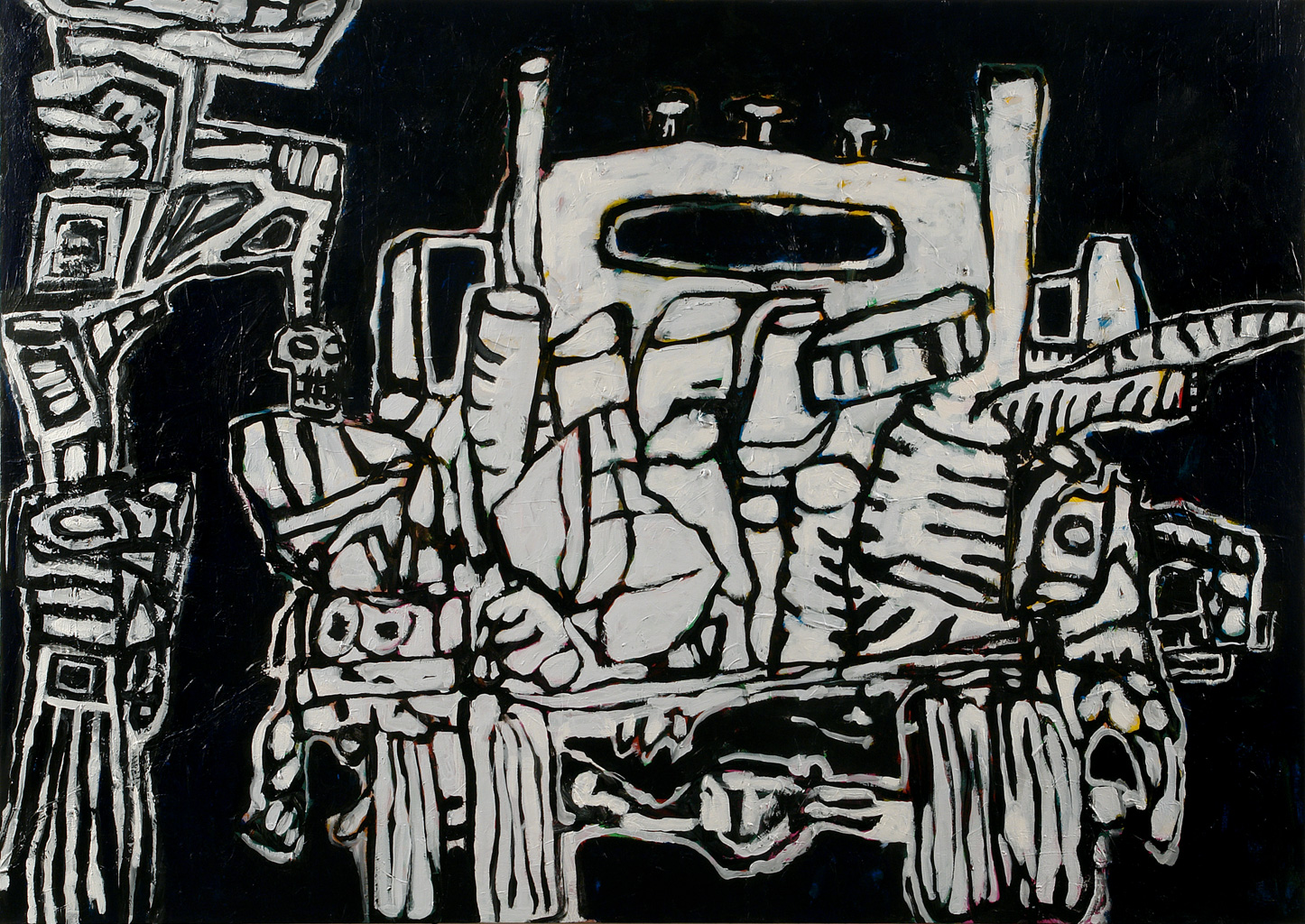

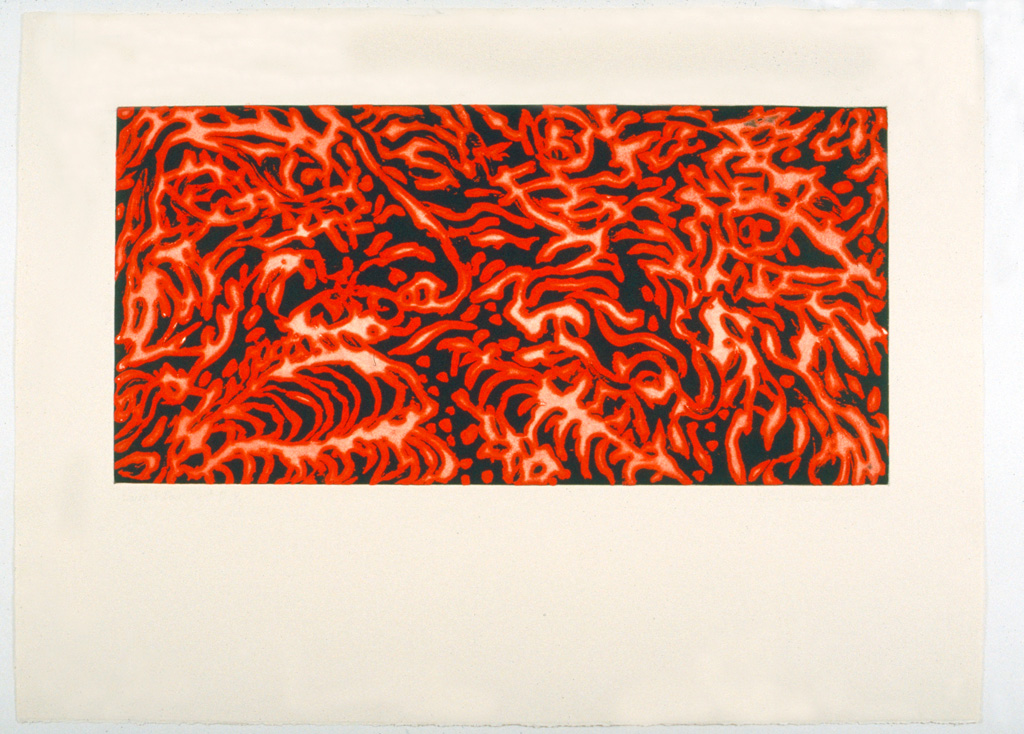

Many such motifs resurfaced in Himmelfarb’s decade-long Inland Romance series, begun in the mid-1990s. These paintings, prints, and drawings revolved especially around the built environment of Chicago, with its traffic, skyline, density, and constant hum. These works are more compact, stripped of excess detail in favor of greater abstraction achieved through the bold, defining outline of strong shapes. At the time, Himmelfarb was mindful of his interest in Joan Miró, a remnant of his 1994 trip to Gallifa, Spain, site of the surrealist’s late pursuits in ceramics, and was favoring as well the naive expressionism of Pierre Alechinsky and Jean Dubuffet. City Circuits (1998, pl. 4) reads as a simple cloissonist design of rounded shapes from which the foregrounded form of a red crane might also be discerned. Similarly, Phil’s Brake and Scrap (2000, pl. 5), with its mounds of colorful arches, is reminiscent equally of Guston and of children’s building blocks in its evocation of a salvage yard. In Inland Romance: Bypass (2003, pl. 6), the heavy-duty vehicle begins to emerge as an isolated image against an abstract field of color, evoking the city at work. Avion (2004, pl. 9), a truck in full-frame profile, is the first true harbinger of the art to come.

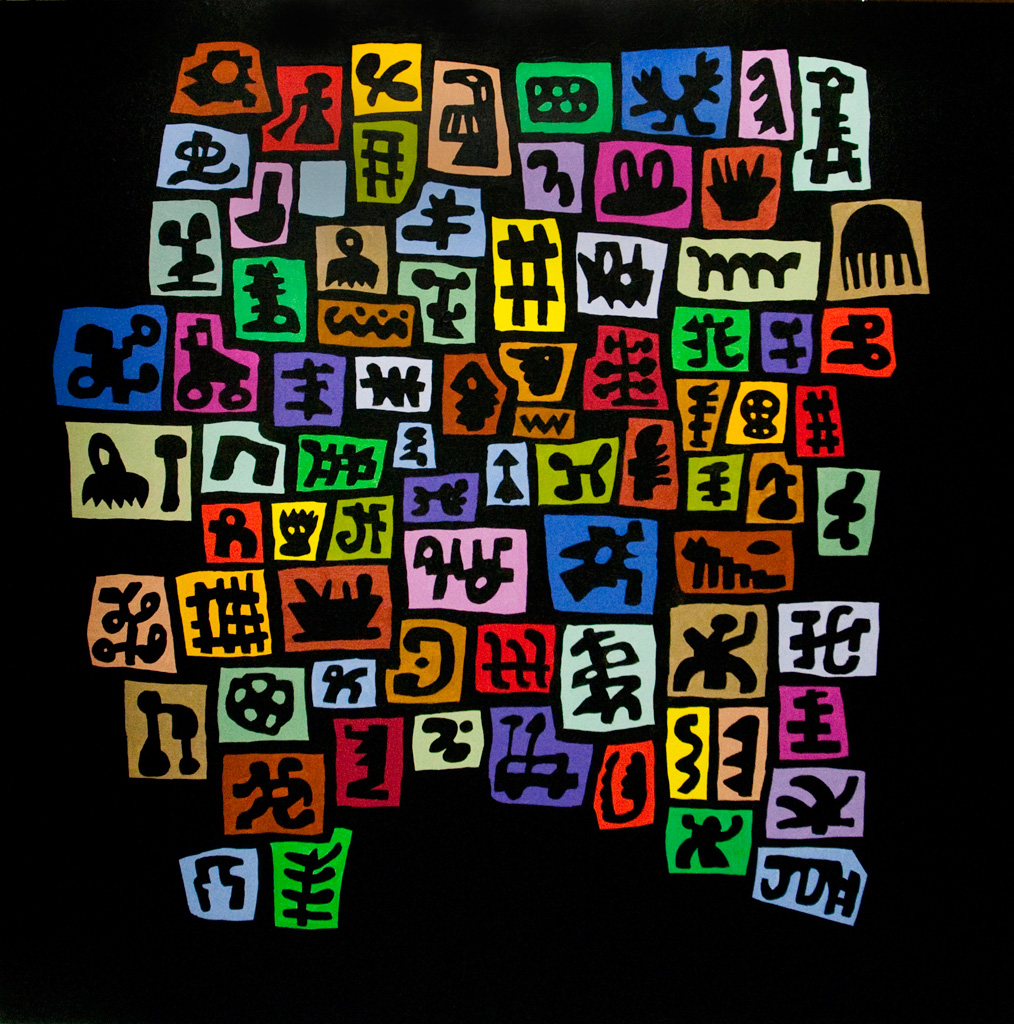

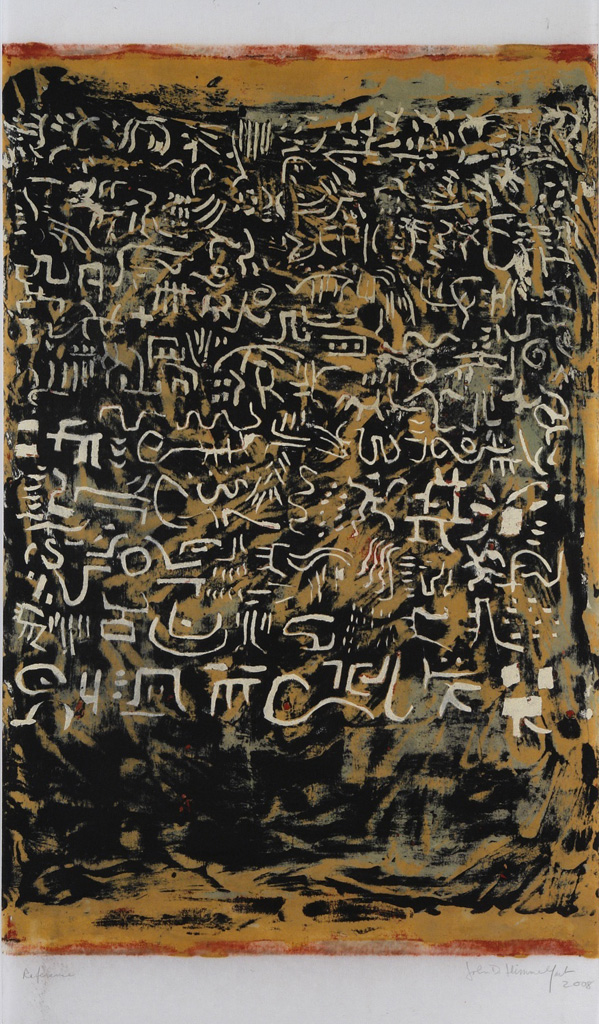

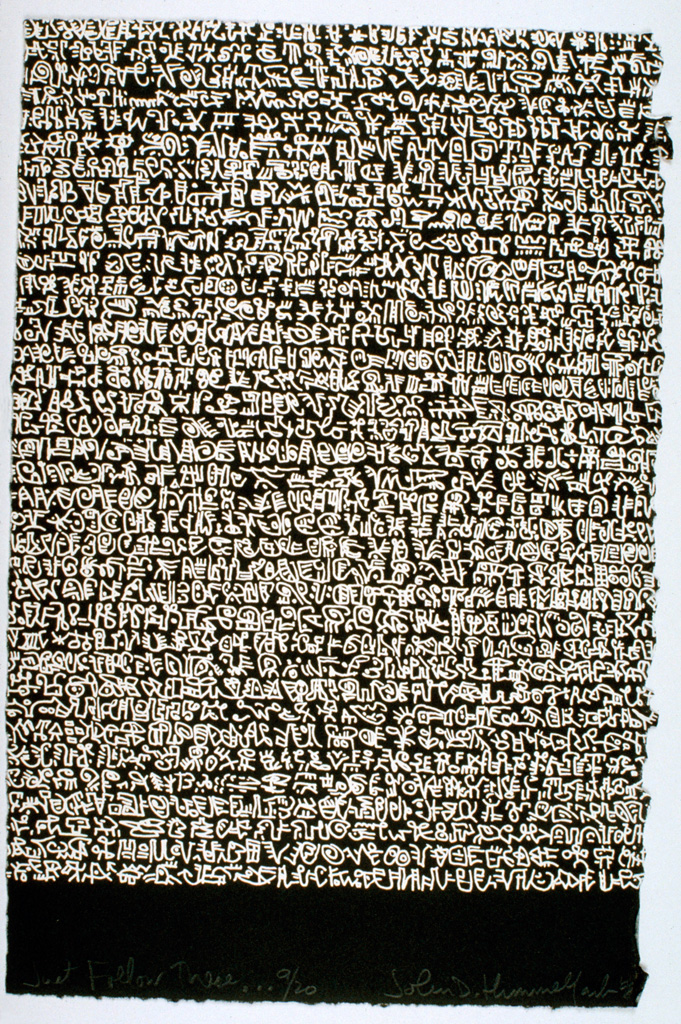

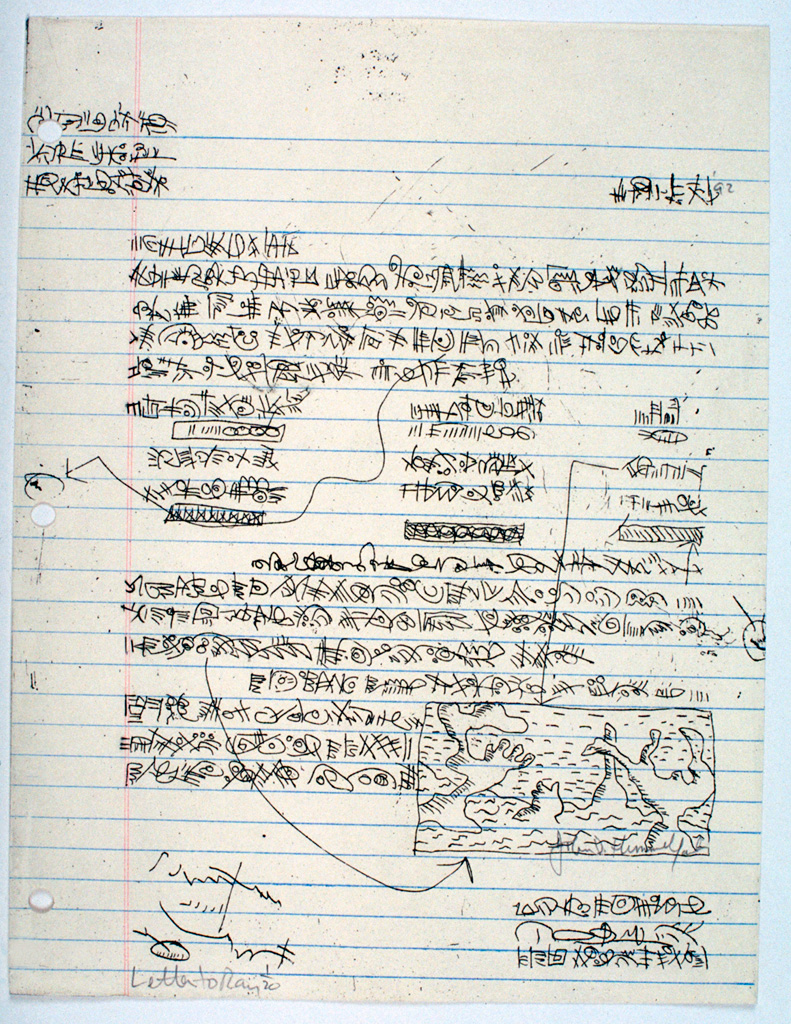

Near the waning of the Inland Romance series, Himmelfarb also began pursuing a more stripped-down approach to mark-making that he refers to as Icons. An interest in Asian calligraphy grew from a fascination with gesture as an authentic element of both design and subconscious expression. Noting the work of such mid-twentieth-century precursors as Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, and Ulfert Wilke, Himmelfarb crafted an invented language of gestures and figures whose rhythms danced across the surfaces of paper and canvas (pl. 8). These works metamorphosed into more hieroglyphic pieces, exemplified by Mobilcaster (2003, pl. 7), in which pictographic elements seem to construct a story using emblematic rather than verbal language. Himmelfarb’s Rosetta stones depart from his previously busier approach to composition, honing in on his desire to work along the fluid edge between visual information and visual art. Hidden among the various symbols and ciphers of these artworks, images of cars, boats, and trucks can be spotted.

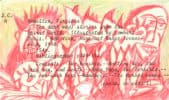

Around 1996, Himmelfarb began utilizing as sketchpads the contents of old library card catalogues long in his possession. Though he seldom deployed the resulting vignettes as preparatory designs for full-scale works, they nonetheless formed a journal of ideas for later reference — itself a kind of tantalizing redeployment of the cards’ original functions. At times, the motifs he drew were a play on the title of a book or subject heading typed on the card. Alternatively, Himmelfarb used the cataloguing data to assign a name to the artwork, which otherwise bore no relationship to the composition superimposed upon it. He found their small size was also optimal for recording shorthand a range of complex ideas, many of which expanded motifs born in the Icons series. It is in this format that the full image of the truck would be resolved and flourish.

In 2005 and 2006, the truck moved to the forefront of Himmelfarb’s work. Catalogue card drawings showing trucks from the driver’s side profile reveal his interest in projecting a range of both character and function. With its big red body and balloon tires, Kidnapping Fiction (pl. 10) displays the delightful charm of a child’s toy. In Haulin Hall (pl. 11), a truck enters a warehouse carting a bed full of cylindrical and other vertical organic forms as if bearing a notional cargo of Isamu Noguchi sculptures. Alaska Natural (pl. 12) and Her Majesty’s Plumbing (pl. 13) are direct renderings of trucks at work, a logger and a crane truck, respectively.

Where these catalogue-card drawings are legible and descriptive, the paintings, prints, and drawings fed by their spirit are more broadly playful, and the truck’s role becomes clear as a platform for Himmelfarb to compose with a variable array of shapes and designs. Compare, for example, a drawing such as Like Lauren Bacall (pl. 14), with its bold, elegant economy of ordered, organic forms, to the bubbly Angel the painting (pl. 15), which resembles a Sunday cartoon of a Dubuffet cargo riding in a Guston-colored world. This scrapper is loaded to the gills with items of precious value to pickers and salvagers, but road hazards and junk to the uninitiated.

The personalities of Himmelfarb’s trucks also develop in these years. To him, they embody common values, emotions, or experiences. Some are emblems of strength and good character: Dedication (2006, pl. 16), Faith (2006, pl. 18), and Courage (2007, pl. 19). A favorite of the artist, Perseverance (2006, pl. 17) is a great illustration of just these principles. It began life as a soft, delicate line drawing on a green field that, in the end, did not satisfy Himmelfarb. Almost as quickly, he brought it back to life by adding the energy and weight of a heavy black outline of a loaded big rig against a busy red ground. The result is a work that seems to be a reinterpretation of Jackson Pollock’s transition from Orozco-influenced dark symbolism to the pure non-representation of abstract expressionism. As suggested by its title, it personifies steadfastness in working until the job is complete, in driving one’s creativity.

In 2007, another major shift took place in Himmelfarb’s approach to his theme. In the winter of that year, the artist began a three-month residency in Wisconsin with the John Michael Kohler Arts Center Arts/Industry program. Begun in 1974, this residency program allows artists unrestricted access to such large-scale industrial processes as brass and iron casting, and to pottery and enamel shops at nearby Kohler Co., internationally regarded designer and manufacturer of kitchen and bath fixtures. Technicians, engineers, and artisans at the plant are available for consultation, but the fabrication process, from start to finish, is purely the artist’s own. The result for Himmelfarb was his first serious, sustained move to working in three dimensions.

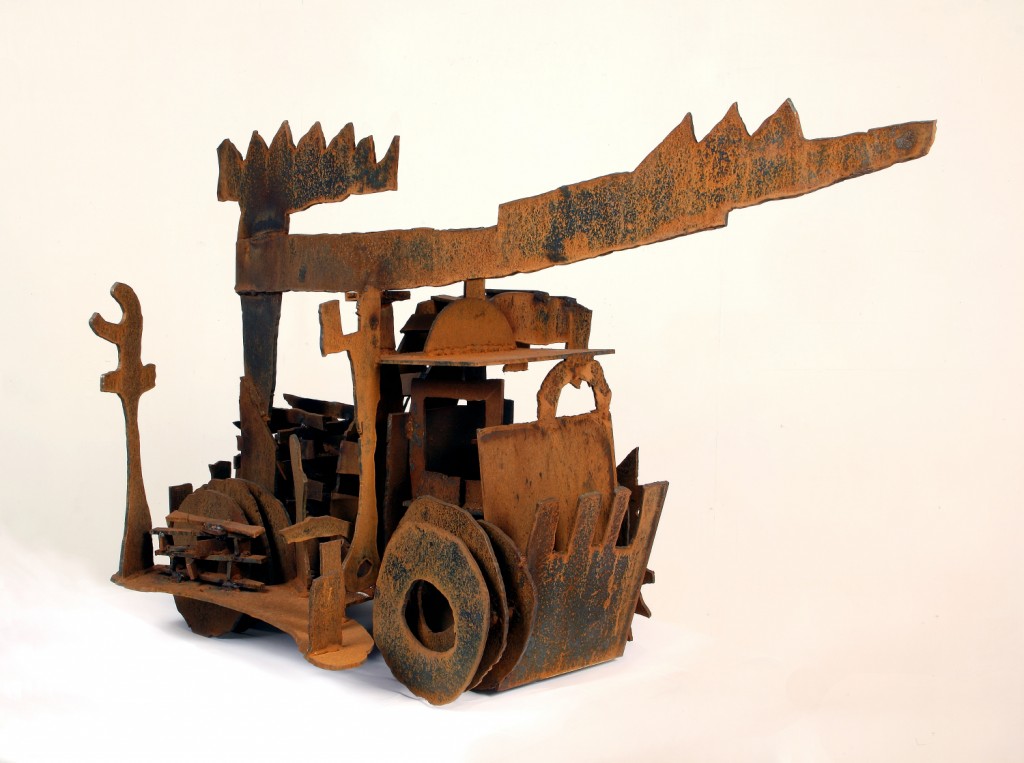

Left to his own devices, Himmelfarb set about making a series of wax and plasticene truck sculptures from which he formed sand molds and cast them in iron, brass or bronze. The twenty resulting sculptures ranged in size from ten inches to six feet. Expressions in form rather than color, most were patinated in verdigris or rust, reflective of their industrial fabrication (medium) and their commercial purpose (subject). Visually, the best descriptor of Himmelfarb’s Kohler haulers is that they are molten and lumpy, not unlike the process that created them. These hulking vehicles are burdened by and often indistinguishable from their creaky freight or mechanical functions (left).

With their new emphasis on weight and mass, Himmelfarb’s truck sculptures meld form and function. The small bronze Fidelity (pl. 20) embodies a very specific concept of a working vehicle with lifting and plowing capabilities, its hard edges rounded off and shorthanded. Mesa (pl. 21), however, changes its attitude from side to side. Seen from the front, the cab is cartoonish, its windows like sunken eyes and the grill a big smile. The driver’s side presents a mountainous old livestock hauler with its rickety wood slats lumbering down the road with its cargo and incumbent “animal emissions.” The rear is less descriptive, with folded shapes cascading off the back like a waterfall. Finally, the passenger side is wide, flat, and relatively unarticulated, like the butte after which he named the work.

Himmelfarb also pushed some sculptures toward full abstraction. In Bird in Hand and Patience (pls. 22 and 23), most distinguishing features are obliterated and the subject is recognizable mainly by wheels and distinctive cab grills. It is almost as if he took the twisted metal of Chamberlain’s steel sculptures and combined it with the freely expressive, process-evident sculpture of Moreover, Himmelfarb had truly found a way to fuse the expansive energy of his drawings into three dimensions.

From this time, the image of the truck was essentially inseparable from any other art making Himmelfarb pursued. He continued to model truck sculptures in 2008 and 2009, mainly in clay, which allowed him to unlock the mass of the cast sculptures into constructed forms that more closely approximated his ongoing work in two dimensions. The multicolor glazed ceramic Lander (pl. 24), with its elliptical tires and wild array of thin vertical and arced slabs in the truck’s bed, relates to the playful finger-painting quality of Frontline (pl. 25). Calvertina (pl. 26), a polychrome ceramic, is more literal in its rendering of a truck outfitted with cement mixer and lifting arm and recalls Himmelfarb’s sketchlike print Outward (pl. 27), as well as his reengagement with the more detailed notational work of catalogue cards such as Taxation Law (pl. 28). With their more stylized and layered components of vehicle and cargo, Modern Burden (pl. 29), an unglazed terracotta, and Truck to Market (pl. 30), a painted ceramic, call to mind model toys and pave the way for later planar constructions.

In 2009 Himmelfarb turned to paintings and sculptures more within the confines of monochromy, typically a feature of his prints and drawings. Forebearance (pl. 31) and Revelation (pl. 32) are large acrylics in black and white, rendered in a Gustonesque style reminiscent of cartoons and early animation. Revelation, in particular, springs from Himmelfarb’s Inland Romance accumulations of repeated forms, and Double Negative (pl. 33) looks like a Jean Tinguely sculpture fell into the bed of a Terry Gilliam truck, betraying a lightness of mood and hand beginning to re-form in the two-dimensional work.

Lingering inside Himmelfarb, however, was the notion that emerged back at Kohler to take his art into the realm of assemblage by using a real truck as an armature for sculpture. In 2008 he found an old International KB-1 pickup onto which he welded a seemingly random, but carefully composed, assortment of implements and mechanisms, including rusty pipes, drums, shovels, and funnels. He then painted the whole thing stop-sign red and aptly named it Conversion (pls. 34 and 35). It is not clear if the freight is of use or junk, if the truck is going to work or the salvage yard. Himmelfarb was reminded of the scrappers he saw on the streets of Chicago, whose loads were piled high with a precarious artfulness, as well as pictures he’d seen of Pakistani and Indian rococo-painted cargo trucks. The result is a work that lies somewhere on a line through the Joads to the Beverly Hillbillies to Mad Max. To the bright and jaunty Conversion, Himmelfarb added a few surprises in the truck’s interior: this old-school vehicle does not have GPS or a DVD player but is outfitted instead in analog with an Underwood manual typewriter and an 8mm film projector loaded with Mack Sennett slapstick comedies.

This same warmth is even more expansive in Himmelfarb’s few paintings from this period. In the large-scale acrylics Hero (pl. 36) and Setting Forth (pl. 37), each from 2010, the mood is felicitous, as trucks chug across fauve-colored landscapes, with coiled masses of stuff springing out of their beds in every direction like a bad hair day. Himmelfarb’s animated drawing style and brushwork accentuate their bumpy journey. It’s as if the artist piled the contents of Inland Romance paintings onto the vehicles and sent them packing.

Himmelfarb followed up his adventures with Conversion by creating a more formal, fully operational work, Galatea (2010, pls. 38 and 39). Here, a classic REO Speedwagon similarly labors under the weight of its odd cache of treasures. A tighter composition than Conversion, the elements making up Galatea are less idiosyncratic and more essential in form (cylinders and cubes), Himmelfarb’s nod to constructivism and to the artisanally sculptural qualities of the vintage REO. The title is a tribute to the myth of the sculptor, who aims to turn a beautiful but inanimate creation into a living thing. Clearly, Himmelfarb’s concept of perfection is not classically ideal, but well-aged and comfy.

Turning back from the street to the studio, Himmelfarb has continued making pedestal-sized sculptures. Several recent works have been constructed of interpenetrating planes of steel or wood that are then assembled into truck forms, as if translating into three dimensions the artist’s recurring predilection for contours and silhouettes. Aiming at greater simplicity, the wildly varying shapes of cargo are replaced by an emphasis on the general configurations of a working vehicle. The rugged fabrication and exaggerated profile of A Bend in the Road (pl. 40) enhance its reading as a construction crane, as does its rendering in Caterpillar yellow. Blue Motive (pls. 41 and 42) and The Road to Herron (pl. 43), made up of jigsawed plywood pieces to which colorful prints have been adhered, have the youthful exuberance of wooden toys. Himmelfarb then scaled up the method and feeling of such sculptures into the safety-orange steel The Road Ahead Leaves a Trail Behind (pl. 44), an evocation of tractors, tanks and other heavy duty moving machines outfitted with track systems. In 2012, he redeployed this work in an installation that, when combined with discarded fuel tanks and oil drums, yielded the artist’s most direct social commentary to date regarding consumerism and the energy economy.

In Himmelfarb’s latest paintings and prints, this same reductive, stylized manner has also taken hold. The trucks are not lost in a beautiful sea of expressionistic brushwork but are silhouetted firmly against simple planes. The screenprint Pipe Down (pl. 46) features a pipe hauler stacked to capacity, rendered in black and white against a stark red background. In its companion piece, Pipe Up (pl. 45), standing tubes constitute the load. Finally, in A Moment of Silence (pl. 47), Himmelfarb’s army-green truck recalls his earlier Icons, as the image is pared down to the frame-filling profile of a vehicle bearing few but essential components. After his sculptural forays with realism, this seems a natural transition.

A decade in, it’s easy to see the expressionistic power and metaphorical range the truck holds for Himmelfarb. And as a viewer, it’s equally hard not to engage with these works. They contain imagery that is so familiar and speaks volumes about the ways life works, addressing the materials society uses (and discards), and our toted baggage that’s both physical and psychological. They look forward, while dragging bits of the past with them, as people are (and art is) wont to do. This is the journey Himmelfarb is making, and since he always leaves room in the cab, the viewer is welcome to hitch a ride.

click thumbnail for larger image

“Why Apples?” Asked Adam — John Himmelfarb’s essay from the book Trucks (2014);

reprinted in the catalog Trucks: Recent Work by John Himmelfarb — Brauer Museum of Art, Valparaiso University (2014)

To my constant amazement, people of all backgrounds and dispositions ask me, “Why trucks?” (Dogs never ask me this, as they share my excitement.) Does anyone ask the artist of still lives, “Why apples?”

For centuries, still lifes were held as a lesser form of art because they seemed to lack reference to intellectual concepts concerning religion, history, and philosophy. Only recently has the still life been accepted as a possible approach to high art. Just in time for my trucks.

An excerpt from my sister Susan’s recent remarks (in a discussion about whether a mystery story can be literature) is germane here: “As a child of two abstract painters, I learned from the air I breathed that content only becomes art when it is given meaning by the form an artist gives it, and that this is as true for literature and music as it is for visual arts.”

My primary driver as a visual artist is to create form that is exciting visually and that suggests content ripe for interpretation through association, metaphor, and implication. I am not concerned with illustrating what we see.

While I played with toy trucks as a child, and included some in childhood drawings, trucks were not major players in my childhood art. Growing up in the woods of DuPage County, west of Chicago, I did hear, more than a mile away and late at night, the sounds of the big rigs headed for the city with cattle and other products from the west. Once in a while, having trouble getting to sleep, I would slip out of the house and walk the distance to Alternate U.S. Highway 30 so that I could see them speeding east as well as hear them up close. The romance of American agriculture, commerce, and industry was contained in these visions.

Only when I became a professional artist did trucks appear as a recurring motif in my work. At the time, uncertain as to whether I could earn enough money to support myself, my plan B was to become a big rig driver. I invented the name “Darryl Licht Transport,” an imaginary cartage firm. “Transport” reflected my desire to transport people through my art, which would remain my primary occupation. “Darryl Licht” referred, perhaps, to the condition of my 1870s Chicago studio. Stationery from this enterprise is filed away somewhere.

The image of a truck appeared from time to time as my oeuvre evolved, much as it had in my father’s paintings and drawings. Our mutual interest seemed to be in the visual stimulation of the colors, shapes, textures, and other elements of visual language to be found in the maw of a garbage truck, the back of a livestock hauler, and countless other complex specimens of the cartage world.

Only much later did I consider the cultural connotations, the significance of what trucks mean to us subconsciously. In the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, I executed a series of paintings called Inland Romance. Chiefly abstracted from the urban landscape of the Midwest, forms generated into cranes, bridges, tracks, roadways and maps, and all manner of urban ironworks, these paintings had layers of network patterns, each extending over the entire canvas.

In 2003, on a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, I saw a painting I’d never seen by Dubuffet, one of the artists who had been most stimulating to me over the years. I do not recall its subject, but it had a soft abstract background of muted color and amorphous shapes on which was superimposed a line drawing in very liquid black paint. The graphic impact was strong. I wanted to make a painting like that!

I immediately went back to my studio, mixed up some blues and greens (as I recalled them in the Dubuffet), and I laid down a patchwork of color swatches of no particular distinction. Over that I began to draw with a liquid black paint, using a thinner brush suitable for drawing.

As usual, I had no particular image in mind. I began on the right side with my industrial forms. The result looked like a crane, and I stopped far short of covering the entire plane with this pattern. It wasn’t enough, so I recommenced drawing beneath the boom of the crane. The truck that emerged delighted as much as surprised me. I felt an immediate visceral connection.

Having experienced a lifetime of art (literature, visual art, music, and theater), I have a great deal of confidence in my ability to sense when a work has resonance on many levels, and this painting, which I titled Inland Romance: Bypass, did. I felt compelled to try creating something similar again and, shortly thereafter painted Avion, a painting whose title may have been inspired by Magritte’s This is Not a Pipe. Not only does the word avion not mean “truck,” the painting is a representation of something more than a truck.

The truck works then exploded rapidly in numbers and materials as I followed this still-unexamined “hook.” To me, the resonance was so clear as to need no examination. However, as these works gained increasing exposure, I was asked repeatedly to answer the question: “Why trucks?”

I explored this question from many points of view, and I found the exploration itself a satisfying endeavor, though the validity of an answer always fell short of any mathematical certainty. The exercise was similar to those I had gone through with other bodies of work that continued over a long period of time. It gave me the same kind of satisfaction I experience in thinking about why a particular novel strikes me as of great moment.

While I have talked to many individuals about these trucks and possible interpretations, I now realize that for me to tell other viewers how to interpret or understand these works is to deprive them of the personal discovery that comes from looking at art.

Now I turn the “Why trucks?” question around. I ask those who query me about my choice of subject matter, “What do you think about when you see these works?” Invariably, I hear, often slowly at first, a series of references both personal and and universal to direct experiences, to literature, music, and to the work of other visual artists.

It is clear to me that I don’t need to tell anyone anything about these pieces. The best thing I can do is to give them permission to answer their own questions. I encourage people to explore my use of visual language and the resulting form. This is where they will find answers. Ultimately, it’s up to each of us to answer for ourselves the questions we have about the meaning of anything, even apples and trucks.

Artist Interview: John Himmelfarb — Judy Chang, The Huffington Post (

Walking into John Himmelfarb’s studio in Chicago is like walking into a candy store, a visual onslaught of colors and excitement, followed by a rush of desire to have everything at once. The subject of an upcoming documentary, his work is included in more than 40 museum collections. Normally you can tell the style of the artist by looking at a few of their paintings. But, the visual vocabularies Himmelfarb employs are so diverse, that it could have been the work of several artists, frenzied cousins even. I caught up with him at his studio to find out more about what drives him and his work.

When did you come upon your unique style of painting?

In 2003, during a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago, I came across a painting by DuBuffet, a favorite artist of mine since childhood. I don’t remember the imagery, only the technique. It had a varied color background over which lay an image executed in a very liquid, thick, black line. I admired the simplicity and effectiveness. Then I went back to my studio, laid down a blue and green background, mixed a fluid black, and began drawing without preconceptions. A truck emerged. Without knowing why, I knew that this was a very important image for me. It has continued to develop over the past eight years.

What inspired you to make Poem of Prospero? What do the symbols mean and what does it represent to you?

Since childhood, the way humans make marks in order to communicate with each other has fascinated me. Early memories to trips of Chinatown are predominately about the signage and the graphic qualities of the newspaper typography. Many of my own drawings since college days have looked like language: pictographic, hieroglyphic, calligraphic, etc.. (A show at Luise Ross Gallery in New York in 2007, Ideographic Sequence, examined this aspect of my work over a 30-year period. Jonathan Goodman covered this in Art In America.)

After traveling to Seoul for an exhibit of my work in 1996, my paintings referencing language changed to reflect the bold and regular quality of Korean commercial signage. Poem of Prospero is an example of such a painting.

What do you think is unique about your process?

I make lists of ideas and works I would like to make. But I rarely look at these lists after making them. They get lost in the creative chaos of my studio. I always have many more ideas of what to do than time to do them. I often ruminate about these for long periods of time and then, at some point, one of them ripens and calls to me urgently for execution. In January of 2010, I created a plywood sculpture I had thought about for some time. When I began, I forgot about everything else in my life and spent three very long days in my studio making Geared Up. When it was done, I immediately realized I wanted to make something in the same vein but much larger. A year went by, while I thought about this and waited for an opportunity to do this. In January of 2011, I drove a load of wood to a studio near Spring Green, WI. I have been renting this space for making large scale sculpture for the last few years. I allotted myself 10 days without interruption and was able to build (composing as I cut) the larger piece, The Road Ahead Leaves a trail Behind.

What advice do you have for aspiring artists and what was the best advice you got from other artists?

When art students ask me how to decide if they should pursue the life of an artist, I suggest that they follow any other direction they can find equally satisfying. Unless that choice is poetry, it is going to be less difficult and more remunerative. However, if someone knows that being a visual artist is the only thing that will make life worth living, he or she should have no fear. There are limitless ways to make this kind of life work, and there is freedom to invent a way of one’s own. No rules.

John Himmelfarb was born in Chicago in [1946] and raised in a woodland setting 30 miles west of the city. He graduated from Harvard in 1968 and the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1970, then settled in Chicago where he has worked since. Since being included in his first national exhibition in 1967, Himmelfarb has exhibited widely throughout the U.S. and abroad. He has received awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Illinois Arts Council, and the Pollack Krasner Foundation. Represented in New York since the 1970s, he currently exhibits regularly with the Luise Ross Gallery in New York …

John Himmelfarb, Selected Recent Works — Geoffrey Bates, exhibition catalog essay, H.F. Johnson Gallery of Art, Carthage College, Kenosha, WI (2009)

One of the first views a visitor encounters as they step over a high threshold and enter the raw space that acts as a foyer in John Himmelfarb’s Chicago studio building is of a pair of library card catalogue cabinets stacked one upon the other. The grid of 300 drawers stands a little over 10 feet in height. The face of each drawer is 4 x 5 ½ inches and displays a brushed chrome pull and knurled screw-top that signifies the end of a rod which extends back through a small hole at the bottom of the hundreds of cards contained therein. The entire effect is that of a visual matrix that subtly provides an introduction to what one will encounter as one explores this center of creativity.

The carefully crafted cabinets, along with their cards, each of which was individually typewritten by an anonymous library worker, have been made obsolete with the advent of computer technology and the internet. Each card possesses a discrete, abstract summary of the book it represents, and a number which locates it within the three dimensional space of the library building.

Information and imagination have been distilled through research and creativity into a collection of singular works, each represented by a card in the catalogue.

Himmelfarb incorporates these cards into his studio practice. He honors their previous life by recycling them as support for drawings he produces in a stream of consciousness that might: pun on the title of the card’s book; use the title as inspiration or, more often than not, disregard the title completely and create an “automatic drawing.” They might focus on a formal concern; study another artist’s approach to a subject; make a to-do list; or capture that sparkling idea that shows remarkable promise but is just as remarkably fleeting. He notes the day and often the moment they are created, providing a sort of visual diary of this thought-processes and concerns over time. Although the library card drawings do not serve as the bedrock source for his artwork, they are a valuable reference tool for him and assist the viewer in following his restless exploration of form. Occasionally they have been translated “verbatim,” if you will, with stunning results (see Borrowed Time, 2007, and March, 2006, library card drawing, Living).

At first glance, it is perhaps surprising that all of the artwork in this exhibition was produced by a single artist. There is no prevailing polemic, no manifesto nailed to the door. The work is consistently outside mainstream approaches to abstraction and figuration. On view are paintings, sculptures, prints, ceramic vases and even tapestries. Many approaches to subject matter are in evidence, but, like volumes in a library, each piece is a carefully considered, discrete work, a distillation of thought carved from decades of experience. Upon closer examination, it is clear that these singular works are united by elements collected in a circulating library of abstraction that the artist has been building, literally, since birth.

History

It is difficult to write about John Himmelfarb’s approach to making art without noting the contribution which his family has played in its development. Both the artist’s father, Samuel Himmelfarb (1904-1976) and mother Eleanor (1910-2009) were accomplished artists whose aesthetic was primarily abstract. Samuel attended art school in Milwaukee, then Madison, Wis., supporting himself as a musician.

He found his way to New York City where he took some classes at the Art Students League and gravitated toward work with architectural firms. Eventually the deprivations of the Great Depression in Gotham forced a return to the Midwest. There, he worked through a variety of design-oriented positions before starting his own firm. His timing was good. Corporate America was beginning to realize that it was often cheaper and more efficient to farm out design problems to specialists. He saw the potential for Chicago’s growth as a national business convention center at mid-century and successfully positioned his business to take advantage of the many corporate conclaves and trade shows that made the city the center of business entertainment for decades.

The Himmelfarbs continued to paint and exhibit widely. They presented work at the Art Institute of Chicago, The Arts Club, and other exhibition venues throughout the region. They provided what must have been a fertile home life for a young man interested in exploring the arts. Himmelfarb writes, “My dad designed a beautiful house full of art, and it was full of art objects, art books, music, trips to theater, dance, museums.” The house was (at the time of its construction) a very contemporary design with an open plan, dedicated studio spaces, and sited on seven heavily wooded acres in Winfield. Young John took advantage of every opportunity to explore the undeveloped region.

Himmelfarb is not a man who “always knew” that making art was his destiny. A college professor encouraged him to commit to an independent study in drawing for a semester. “After a couple of weeks of intense drawing, self directed, the light bulb finally lit!” Once committed, he staked out a difficult position that virtually all of his associates except his parents discouraged—he wouldn’t teach, he wouldn’t design, he would make his living making art.

This workmanlike approach has served the artist well as he has built an exhibition resume that spans over 87 solo presentations, numerous public and corporate commissions, many artist-in-residence positions, and inclusion in major museums’ collections throughout the U.S. and overseas during the past four decades.

Growing up among artists who have made a practical choice to make a living through design and not chosen art as a life-style furnished Himmelfarb with an unpretentious sensibility in his dealings with the world-at-large. Educated at Harvard, he has always shunned irony-laden approaches to expression in favor of an almost blue-collar work ethic whose aesthetic celebrates thought and personal investment. Absent is the affected rebelliousness and signature trademark many artists feel is critical for recognition. Citing the shock of the new as the driving force behind artistic change during the 20th Century, the artist recently commented, “My point being, I suppose, that choosing an approach to art that is firmly based in ‘visual language,’ refers to and builds on the past, and eschews the pursuit of ‘firstness,’ is the ultimate rebellion, paradoxically.” He rejected a move to New York and has always approached his work with a Midwestern practicality, purchasing a dilapidated 4-story brick building in 1971 and taking a year and a half making it habitable as both work and living space. This prescient move, made to establish financial stability and escape the cycle of gentrification and escalating rents that so often accompany artists’ urban homesteading, later allowed him to buy a building where he now has his studio.

Recently, Himmelfarb’s work has moved in several different directions while maintaining contact with basic stylistic signatures.

Correspondences

Many artists find comfort and creative drive through a narrow focus on subject matter or technique. Each of Giorgio Morandi’s still life paintings tells a separate truth about form, light, color, paint application, and patience. Josef Albers spent a lifetime parsing the relationships of hue, value, and saturation within a square format. Other artists seek to experience the challenge of unfamiliar media, embracing awkward moments of uncertainty as they discover new truths about their personal aesthetic universe. One of the most fruitful avenues of access to develop an appreciation of John Himmelfarb’s work is to concentrate on continuously circulating relationships of fundamental elements over time and across media. The artwork selected for this show represents the disparate approaches to media, yet the consistent aesthetic sensibility, the artist has explored over roughly 10 years as he has enlarged his technical palette.

Himmelfarb has made a career of turning two-dimensional space inside-out and topsy-turvy: drawings so dense with imagery they appear to be calligraphy; calligraphic paintings that balance mark and space in an ambiguous dance of push-and-pull; colorful iconic forms that might be pictographs, could be figurative, might be pure abstraction; matrices of nervous line that are layered with residual forms/shapes from earlier paintings sometimes asserting themselves as foreground and sometimes acting as ghosts of paintings past, pentimenti offering quiet testimony to his persistent search for balance.

Wax Eloquent (2007) provides a clear example of one approach to playing with space. Many of the shapes reflect sources from the “real” world: cannon, trees, dogs, a ship. But the space surrounding each of the forms also creates a dynamic, abstract shape. It is through his close attention to how line and space define form that Himmelfarb’s art achieves its restless movement and continuous, dynamic sense of re-invention.

The Truck Arrives

Himmelfarb began his considered exploration of sculpture by casting iconic pictographic forms in bronze. Echoes of these shapes had been present in his painting since the mid-1970s and are evident in works such as Tool Talk (2001) and Mop (2003).

The resultant sculptures reflect their origin in the artist’s continuing interest in calligraphic marks (see Reference, 2008). High Style (2003) appears to be pulled from a Chinese scroll with its crosstrees of bronze enlivened by gestural surface treatment. Party Line (2003) uses a broad curve to imply negative space even as it puns on telephonic history and politics. By the time he arrived at Stretch and Rock Me (both 2003) he was making figuratively abstract objects that successfully activate the space surrounding them while remaining thoroughly flat forms. Leaning in Your Direction, also from 2003, is heavier, both physically and conceptually. The figurative work evokes thoughts of an archaic Northern European figurine with its broad planes, carefully placed holes, and sensitive patina.

Two library card drawings from 2005 seem to indicate a shift in attention toward a quintessentially American subject matter. On 7/24/2005, a tow truck appears alone inside a frame of iconic pictographs. And in Paris on 7/26/2005, on a library card for “The Mammals of North America,” by E. Raymond Hall, a pencil drawing incorporates arched elements of his Inland Romance series paintings from 2003 as cargo for what may be a firetruck. On the back, the artist has written “at the restaurant near filles di cavaliers 10 PM ONZIEME/ART; 80 RUE Amelot 75011; 0143 38 8525.” The definitive nature of his legend affirms the significance of the moment.

Perseverance, a painting from 2006, reflects his blossoming interest in the subject. The wall-sized painting is an energetic accretion of jots, marks, color shapes, and a truck image that seems less of a picture than the result of flotsam coalescing at the surface.

Trucks continue to appear with regularity on library cards throughout the period from 2005 to the present. But it was a fellowship at the Arts in Industry program in Kohler, Wisconsin, during the winter of 2007 that allowed the artist to begin seriously pursuing a three-dimensional approach to this new topic. Immersing himself in the experience, he worked twelve to fifteen-hour days throughout the three month period taking every advantage of the remarkable opportunity and exploring varied approaches to ceramics, welded steel, cast brass, and cast iron.

Greek Opera, Reefer, Prepared and Bird in Hand (all 2007) emerged from this period of wide-ranging creativity. Greek Opera, with its six-foot length, is a hulking, militaristic amalgamation of Humvee and Mesa Verde ruins and is on long term loan to a private collector. Reefer makes reference “to a refrigerated truck, but also to a reef, like you’d find in the ocean,” the artist said recently. The organic work, with its drippy, droopy, crusty forms appears to have been dredged from a South Pacific underwater graveyard for World War II relics.

Himmelfarb quickly began to refine and apply his characteristic spatial game to the new medium. The viewer will make out the restless line threading throughout his oeuvre in both Prepared and Bird in Hand. But, Bird in Hand, in particular, announces a familiar, yet freshly articulated, voice.

We immediately recognize the old, beaten-up truck. However, Himmelfarb has once again turned space inside out, or more correctly, abandoned space as we normally experience it and chosen to use the truck icon as a platform for experimenting with layered space and line. It’s as if Irene Ryan and Georges Braque got together to design a moving van. Himmelfarb’s gesture, his calligraphy, his pictographic shapes and ambiguous space are all there — but now it’s 3-D.

Recent Paintings

A comparison of three recent paintings provides insight into Himmelfarb’s general attitude toward art-making. Despite employing different approaches in each work, none are seen as more or less precious than the other.

Much of the artist’s attention in the past two years has been spent on exploring and enlarging his understanding of the truck as a subject. 2008’s Inventory functions much as Wax Eloquent — a listing of approaches and images that, this time, have to do with trucks. Some are dark on a light ground, some light on a dark ground, some frontal, some side view. Himmelfarb has lifted the lumpy-bumpy surface treatment from the three-dimensional work and deftly transposed it to canvas with a sense of urgency, layering and incorporating the drips and splashes that occurred as he attacked the surface.

Dug In (2008) is more like a blind contour drawing where the student’s pencil carefully maintains contact with his page as he draws from the nude without looking at his results. Himmelfarb’s line is no less engaged as it rambles across the surface creating luscious shapes and forms that at first glance seem as though they might define familiar cargo, but upon closer examination, dissolve into a loaded brushmark that’s as delicious as Welch’s grape jelly.

With Revelation (2009), he combines aspects of Inventory and Dug In to create a work that marries line, shape, and form with content—here the viewer experiences parts of the architectonic load visible in the library card drawing from 2005 and bits and pieces of other Inland Romance paintings, as well.

Rewriting

The time at Kohler casting his fleet of trucks whet Himmelfarb’s appetite for challenge. In 2008, he acquired a 1949 International Harvester model KB-1 pickup with the idea in mind that he would create one of these works in the “real world.” The viewer’s experience of Conversion (2009) shifts through several phases: first, there’s the curiosity factor — What is this stuff? Gradually, one begins to pick out automobile grilles, two-man saw blades, farm whatchamacallits, and other obscure pieces of sculptural metal that have been welded and painted in a seemingly helter-skelter fashion. An antique typewriter and 16 mm projector imply the presence of a narrative known only to the artist. Himmelfarb addresses automotive history by making this a lil’ Red Pickup.

Finally, as if the viewer’s eyes are finally getting used to the dark, the ‘art’ part of the piece begins to surface. Here are shapes, lines, and gently curved planes which provide subtly graduated value relationships in abstract spatial arrangement. Here are forms and shapes that have iconic meaning and identity in their other lives, lives which have been subsumed in service to the composition at hand. Here is a sculptural realization of many of his painterly ideals. Once again, he’s checked out his own book, rewritten it, and presented it anew.

Over the past four decades John Himmelfarb has built a complex and compelling set of approaches to creating abstract works that remain firmly outside mainstream stylistic impulses. While tangling and teasing out iconic images in the language of abstraction in one series, he has incorporated references to real world objects such as plants, buildings, landscapes and trucks in other series of works. His complex vision continues to unfold a rich dialogue of color and theme that, together, form a sumptuous library of recurring, yet freshly resonant, images for the viewer to ponder.

click thumbnail for larger image

John Himmelfarb: Multi-Dimensional — Susan Aurinko, exhibition essay, Flatfile Galleries, Chicago (2007)

Studying a painting or print by John Himmelfarb is a little like unraveling a sweater; the more you deconstruct it, the less it looks like what it was. His work is tightly constructed, meaningful, and defined by both deep thought and whimsy. Similarly, it is both quirkily conceived and formally perfect. Himmelfarb loves to play, with titles, with concepts, and with materials; the serious business of art rendered light-hearted. For example, take a recent four by eight foot wood cut. Why not? And to make it even more interesting, why not print it on a four by eight foot sheet of wood veneer, then mount it on the back of the block and suspend it like a screen in the middle of a room? — Himmelfarb-thinking in its purest form.

Himmelfarb’s pieces are filled with questions, rife with mystery; unknown texts sidle up alongside invented icons and fill whole sheets with imagined dialogue. These visual love letters are testament to his lifelong infatuation with material and form. In his more recent foray into bronze, iron, and aluminum castings, and working with clay, the iconic texts take three-dimensional form that captivate both mind and hand with their wonderfully raw, brut textures and beguiling patinas. What is so intriguing about Himmelfarb’s work is that he seems equally at home in all mediums. He forms a creative question and shows us that there are many roads leading to the answer, all of them valid, and all of them intensely tempting.

Many simultaneous projects dot the cavernous but highly organized studio. Tiny delicate drawings on library cards grid a tabletop, and a twenty-seven foot long, ten foot high, wildly gestural painting stretches the length of the studio like a billboard. There are waxes in the process of becoming bronze castings, and plates in the process of becoming etchings. Each surface holds a work in progress, for Himmelfarb is nothing if not prolific. His commissions are as diverse as his personal work, from cast bronze gates or hand crafted glazed iconic tiles for homes to mural sized public art for airports, libraries and universities, the list goes on and on, and in each case, new territory is charted, an additional medium is learned. Himmelfarb is a scientist and a sponge, a pioneer and a prophet. He experiments, learns, discovers, and generously shares his unique perception of the world.

On my first visit to Himmelfarb’s studio, I was fascinated at the vast quantity of remarkable work that he has created over a lifetime. Yet, as diverse as his art is, there are threads running through it all that stitch it into one unified body; there is no mistaking any of Himmelfarb’s oeuvre for anyone else’s. He is one of a kind, a Renaissance man let loose in a world of art supplies, fearless, maverick, always on to the next thing, yet remaining true to this vision.

John Himmelfarb: Long Overdue — Matt Freedman, catalog essay for Long Overdue at the Phyllis Stigliano Gallery; and reprinted in Art-TheMagazine.com (Apr 2005)

John Himmelfarb has papered the Phyllis Stigliano Gallery in Park Slope, Brooklyn, with some 200 small images drawn on old library catalog cards. This casual deployment of casual work allows us to look in (listen in?) on the artist talking to himself, working fast and playing loose with ideas and impulses, producing objects that are once utterly complete statements and also tantalizing ephemera of pure (re)search.

There is something self-sufficient and essential to observe in these pieces. What is displayed is a statement of the artist’s core principles that could perhaps only be made in these unguarded moments. The ideas presented in works of greater visual formality may gain persuasive authority through their association with a fully-realized synthetic reality, but by the same token the very craftsmanship of that artistic seduction places us at a calculated distance from the mind and heart of the creator. Which is why the transparency and contingency of these quick small studies is so beguiling. We are invited to travel deeper into the artist’s head than he normally allows us to go and to see, if not another world, then this one through alternate eyes.

But we are not merely-only-looking at sketches. Himmelfarb intends for us to understand the card drawings as ends in themselves. He wants us to see this playful meta-dialogue as the essence of his practice. The play is the thing, not the production. The artist, however, is slyly having it both ways: while Himmelfarb’s cards announce their presence as the effluvia of a winsome and active imagination, their collective appearance on a gallery wall reifies the imaginative play that produced them in the first place. The mass of cards is impressive and overwhelming; a respectable and “traditional” work of art in its own right. Collectively, the cards provoke an emotional and esthetic response that individually they shy away from.

This paradoxical melding of the self-effacing and the grand, the deliberately modest and the deceptively ambitious nicely personifies one of the many bracing tensions in Himmelfarb’s art. Bipartite themes run throughout the artist’s extensive and diverse body of work, as does the impulse to string stuff together, to utilize connections and contingencies as animating agents. Himmelfarb constantly fragments and connects as he doodles his way into massive murals, cartoons his way into pathos, layers whimsy and flippancy into Bosch-like complexity, hilarity and terror. All the while, the artist keeps his poker face and plugs relentlessly away with a studio practice that emphasizes, unfashionably enough, substance over style.

The initial and perhaps lasting impression is of a mind — a mind gently unhitched to conventional flows of logic and propriety perhaps, but a comprehensibly analytic mind nonetheless — whose work is play. Everywhere in the room we are reminded of the inductive and sequential process of the artistic imagination at work, a process Himmelfarb himself subtly pushes upon us as a theme in his practice as important as the actual images that he generates. In the library catalog cards, the linkage of idea to image is largely spatial and schematic. Sometimes, the artist plays off of the content of the cards for inspiration; a word or a theme or a name on the card inspires a drawing, but, just as likely, he responds to the layout of the text itself on the card. The dispersal of black type against white space creates limits for drawings and, sometimes a formation of type, like a cloud, inspires an image on its own. Each card is a separate planet, close but no cigar to the next one over. Within each card we are taken on a delicate little safari, each one inspired by some tenuous ephemeral impression.

It is interesting that Himmelfarb regards the drawings as something akin to diary entries; they are highly responsive, not just to the graphic or narrative qualities of the cards they occupy, but to work of other artists or writers he is encountering; sometimes they are simply drawn from life. They are done away from the studio mostly, and they serve the artist as true mementos, reminders of experiences instantly distilled into line. Collectively, the effect of all these little report cards is quite overwhelming. The wall shifts from small scale to large, a tour de force of imaginative suppleness.

But if the collective presence of the cards somehow legitimizes them as respectable artistic endeavor rather than a series of inspired doodles, so, too, does their massed presence threaten to fool us into assuming that any mind producing so much must operate according to an obsessive structure. We must remind ourselves of the gentle playfulness that produced each little picture. Think, perhaps, of those old pictures of annual food intake of the typical American family, so popular in the self-congratulatory 1950s. Four small people in a warehouse filled with hundreds of roasted chickens, gallons of chocolate milk and tons of Rice Krispies. We ate all that? Yes, but not all at once. The accumulation of any quotidian exercise is formidable over time; seeing it all at once is overwhelming but perhaps misleading: things, inevitably, add up.

At the core of Himmelfarb’s playful practice is the idea of noble work; art making labor as a sort of joyous, defrocked priestly activity that is both its own reward and the path to esthetic and spiritual enlightenment.

Matt Freedman is an artist and writer living in Queens, New York.

The exhibition is accompanied by a small catalog/book featuring the above text and life-sized reproductions of Himmelfarb’s drawings. Price: about $40.

click thumbnail for larger image

Recent Paintings: 2000-2001 — catalog essays, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL (2005); in cooperation with Jean Albano Gallery, Gallery 72, Peltz Gallery, Spaightwood Gallery, Stewart & Stewart, William Havu Gallery

Excerpt from the catalog: American Graffiti(2001)

Himmelfarb’s painting and prints embrace an internationally recognised aesthetic vision, yet ultimately it is the small detail of this monumental conception and scale that reveals the artist’s disposition. Viewing the art of Himmelfarb evokes a joyful sense of musicality, the figurative and the lyrical. Himmelfarb, in fact, invites the gallery visitor to participate in the singularity of his world and celebrate its beauty and monumentality. It is this notion of the grand vision and the intimate detail of the artist’s world that … transcends recourse to formula. Himmelfarb’s art profoundly reveals what the artist knows about the world around him, and elegantly and discerningly articulates this vision …

—Warren Feeney, Director, Centre of Contemporary Art; “American Graffiti,” 2001, Centre of Contemporary Art, Christchurch, New Zealand

Excerpt from the catalog: John Himmelfarb: Inland Romance(2001)

Since 1993, John Himmelfarb has been working on the series Inland Romance, a sequence of paintings reflecting the artist’s romantic attachment to the city of Chicago. Like Carl Sandburg’s poem Chicago, Himmelfarb’s artistic vocabulary relates to the “down to earth” elements of the urban environment. The majority of these elements are inspired by industrial forms, such as venting systems from factory roofs, chimneys, elevated structures, cranes, scrap yards or railroad equipment. Others relate to the rapid rhythm of the city through aerial views that captured the ever-changing patterns of rivers, roads, bridges and paths.

In the introduction to the book Chicago Stories: Tales of the City, Chicago author Stuart Dybek characterizes the local writers as a product of the unique urban environment and their tendency to romance the city. “Chicago,” writes Dybek, “is an outlook from the perspective of the country’s third coast, a sweet water inland sea surrounded by prairie, a locus at the center of America where there’s not much patience with fads or pretension.

“Finally, at the core of the Chicago Tradition there is an insistence on sentiment, ” he continues. “Not on sentimentality, but on basic emotion, the complex mix of passion and empathy we term the human heart.”

Himmelfarb’s concept of Inland Romance corresponds to Dybek’s perception of the Chicago writers. “The romantic attachment to the region,” says Himmelfarb, “is the reason I am here, and my paintings reflect where I am creating as well as who I am. The two are connected.”

—Nathan Harpaz, Curator, William A. Koehnline Gallery, “John Himmelfarb: Inland Romance,” 2001, William A. Koehnline Gallery, Oakton Community College, Des Plaines, IL

Excerpt from the catalog: John Himmelfarb: Inland Romance(2001)

Three large, colorful, and related paintings will be seen in the process of being executed by one of the most skilled and thoughtful painters now working in the Chicago metropolitan area. Most significantly, observers will have the privilege through this showing to acquire a first hand insight into the nature of the creative act, and the process of improvisation, adjustment and revision, which poets and novelists, composers, playwrights and architects face daily in the act of creation.

Himmelfarb’s commitment to this “on site” painting display is a courageous expression of the confidence gained in his years of studio practice, the poise and experience he has found in posing creative problems for himself and his success in carrying them through to a professional conclusion.

—Gerald Nordland is a former director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Washington (D. C.) Gallery of Modern Art. He has written numerous catalogs and books on 20th-century art. “John Himmelfarb: Inland Romance,” 2001, William A. Koehnline Gallery, Oakton Community College, Des Plaines, IL

Excerpt from the catalog: American Graffiti (2001)

Chicago, where Himmelfarb was born, trained and lives, is at the heart of much of his oeuvre. He uses this great modern city as a creative muse while successfully avoiding cliché. With a broad Abstract Expressionist accent, Himmelfarb often crosses the stylistic and thematic paths of others without forfeiting the integrity and originality of his work. He embraces the city with enthusiastic candour, celebrating its formal qualities while speaking of human habitation and endeavour.

Himmelfarb’s new visual language combines vibrant colour, eloquent line, painterly brushwork, dynamic composition and a grand scale, capturing something of the city’s essence. The dynamism of city life pulses through, but unlike the Futurists, underlying political motivations are absent. Indeed, if there is a spin, it is one of genuine affection for the city, its energy and activity.

—Esther Venning, Curator, Centre of Contemporary Art, “American Graffiti,” 2001, Centre of Contemporary Art, Christchurch, New Zealand

Wall to Wall: John Himmelfarb — Matthew Rose, NY Arts Magazine (Dec 2002)

The artist, now a well known quantity throughout the Midwest and New York, has been painting the emotional chutes and ladders of life on the planet for more than thirty-four years.

If you were at the Koehnline Gallery in Oakton College, in Des Plaines, Illinois on the 6th of September, 2001 you would have walked into a large space carrying your cocktail and noticed two big canvases by John Himmelfarb, and a third canvas, 11 1/3 feet by 25 feet — completely blank. A few minutes later, a man mounted a ladder and began to punctuate this empty field with blue vertical stripes.

This was Himmelfarb’s first real public act of performance painting. Although the artist performed a large scale public performance painting in the 1980s inside the Toy Bank in Sioux City, Iowa, the Oakton Circle canvas, a tremendous effusion of color and shape, was set up to put the painter directly on the stage of art making. But it was hardly a gimmick. Five days later, with the September 11th attacks numbing the American population, to do anything creative seemed an act of defiance. On the 18th of September, when Himmelfarb continued working on the piece — and continued to perform for the public, most visitors saw in his work a reaction to the September 11th attacks.

Working two days a week until the 26th of October when the show came down (and Himmelfarb completed the work), the bulk of comments by visitors, students, curators and other artists centered on the emotionalism of the work, and how it was one American artist’s take on the world, now that America was deemed vulnerable, and living its life with its very open wound.

Himmelfarb’s most recent live giant painting project at Indiana University Northwest in Gary was called “John Himmelfarb Wall to Wall,” and ran from September 25 through October 25 2002. The canvas, a 9-foot by 65-foot monster, was installed and primed on September 30, with the painting completed on October 15.